Education makes one think and helps one to act. Knowledge and skill are the corollaries of thinking and acting. They feed upon each other.

The head and the hand had always worked in symphony to produce food, weave cloth, build structures, sing songs, create music and launch vehicles on land, water and in space — to attain progress and continue on an upward moving spiral, or a downward spiral as some environmentalists would argue. At some point in time, though, the wall between the head and the hand became pronounced by the emergence of guilds for crafts and arts and universities for theology and philosophy. The great divergence in India In India, two great divergences happened.

The first was religious sanction accorded to birth-based occupations, despite the possibility of Jatis moving up and down the varna system. The overall system classified professions on a graded scale of purity and forbade interactions between jatis, resulting in silos that got solidified first and ossified later. The idea of impurity of professions over the millennium is so deep rooted that it is banal now.

The second accelerating factor was the western world’s consistent effort to destabilise and destroy local productive knowledge and patronage networks, as well as the total bypassing of India from the forces of industrial revolution. This has resulted in a system that glorifies rote learning especially in a language that is foreign to a substantial majority of the country. By categorising education as distinct from skills, it has made the distinction between head and hands so deep that one does not speak to the other.

And one is distinctly superior to the other. The disdain for physical labour is deeply linked to the disdain for those performing it. Our level of productive forces is such that Prince Philip commented on a loose fuse box in Scotland that it appeared to have been put together by an Indian.

Jugaad has become our national pride though it’s only a compulsion. Why is our education stunted? World over, TAFE and TVET — systems of technical education — have evolved so much that the distinction between them and higher education is almost nil. But in India, in discipline after discipline, we have built silos that do not talk to each other.

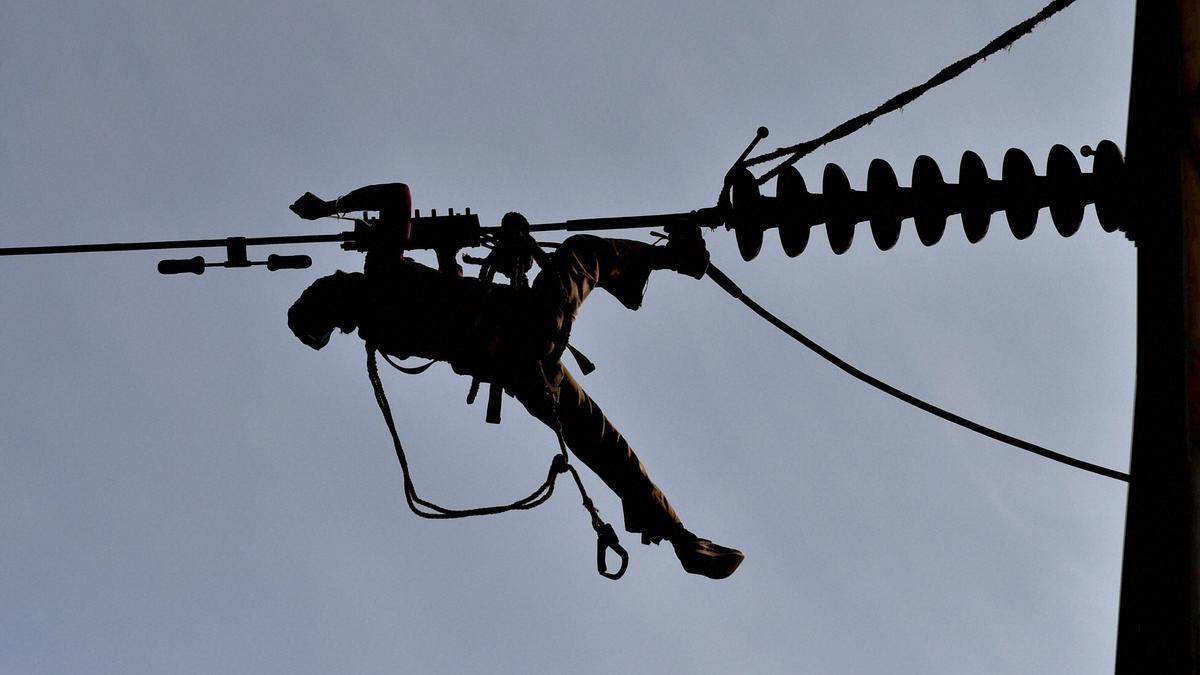

Take electrical engineering as an example. To join as a helper in the electricity board you need no education. To be a wireman, you need to pass Class 8 and get a one-year ITI.

Most do neither and learn on the job. To be an electrician Grade II you need to pass Class 10 and do two years ITI. The wireman has no future education possibility.

The electrician Grade II can theoretically pursue four years of part time polytechnic, but access and availability are almost nil. Only a microscopic minority of plumbers, carpenters, masons, electricians and mechanics in our country get education. Most of them learn on the job and none of them barring the mechanic (only four-wheeler, not two wheeler) has the possibility of furthering his prospects by further education.

No link between education and experience Further, the linkage between experience and education is almost nil here especially in the public sector which still remains the largest employer. For instance, a Rajasthan State Gazette notification for qualification and eligibility for its electricity board recruitments says to be a foreman in the electricity board one needs to have a diploma plus one year of experience or secondary school plus ITI plus 11 years of experience. So two years of some education is equivalent to 11 years of work experience.

No other country would devalue real work like this. No wonder the country’s youth go for a B. Tech that does not give you a job rather than an ITI that might put food on the table.

Contextual education I spent over two years intermittently in a State with a large tribal population, trying to put together a career guidance programme for the children of the State. A relook at the vocational education system especially at the school level was part of the brief. The system offered banking as a subject for children in a district where the nearest ATM was 50 km away.

Tribal medicine, tribal food, value added crafts and value added forest produce were all total anathema to the framers of their education system. The children had tremendous ability to work with their hands. Their ability to reproduce a product just by looking at the process for a few minutes was astounding.

But they were forced to read about Akbar and Indian polity, bad English, banking and beauty. No wonder most failed in their exams. Professor Dharampal, a Gandhian, looked at indigenous knowledge systems a little too uncritically.

A.K. Perumal, a researcher in Kanyakumari, who didn’t know Dharampal, chronicled the efficient water harvesting, storage and management systems of erstwhile Nanjil Nadu in today’s Kanniyakumari district of Tamil Nadu.

Mahatma Gandhi proposed Nai Talim as a system of basic education in which knowledge and doing are not separate. It can serve as a good starting point. We have all the knowledge needed to reboot.

A new education must start from there. (The author is an educationist and founder and former editor of Careers 360) Copy link Email Facebook Twitter Telegram LinkedIn WhatsApp Reddit education.