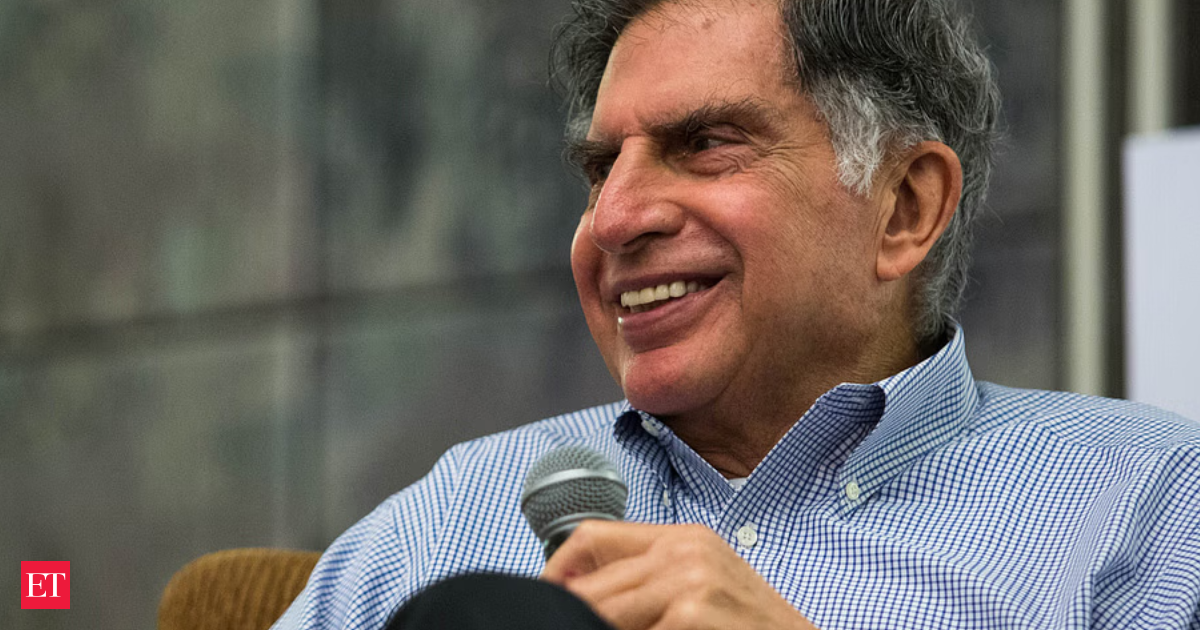

India marked Ratan Tata ’s death on Oct. 7 in a very Indian fashion. His body was displayed in a glass coffin draped in the country’s tricolor flag.

A vast crowd ranging from grandees of business, politics and Bollywood to regular people who testified to Ratan’s innumerable kindnesses gathered in the sweltering heat. A police band played music, and the state flew its flag at half-mast. Yet Ratan was as much a global figure as an Indian one — a titan who devoted his life to transforming the Tata Group from an idiosyncratic Indian conglomerate into a global behemoth with operations in more than 80 countries.

(I will call the titan “Ratan” not out of over-familiarity but to avoid confusion with the company of the same name.) The Indian mourners might well have been joined by the good and great of the globalization movement — corporate giants such as Bill Gates and Larry Fink and globalization gurus such as Harvard’s Michael Porter and the New York Times’s Tom Friedman. When Ratan took over the conglomerate from J.

R.D Tata in 1991, India was embarking on the most important revolution since independence, ripping up the License Raj and embracing globalization. He recognized that this was both a threat and an opportunity: a threat because the company’s business model might be rendered irrelevant, an opportunity because he had a whole world to win.

Tata Sons had grown to greatness by doing two things: playing a leading part in nation-building, first under the Raj .