The CAGED chord shapes can be a great way of learning the geography of the fretboard. The shapes, both major and minor, occur in every position and key just like the pentatonic boxes. In fact, they form part of these very same patterns but in a far less linear ‘two-notes-per-string’ way.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of regarding the CAGED shapes purely as chords. After all, where would we be without our E- and A-shape barre chords? But just as some pentatonic shapes fall more easily under the fingers, some chord shapes are easier to shift around than others. Once you move out of open position, the C and G shapes can become very impractical, with D running close behind! Generally, us guitarists accept that playing these as full chords isn’t a great (or widely used) option.

You wouldn’t try to play every note in a scale simultaneously, so why not apply this attitude to the CAGED chord shapes and strip the C, G and D chords down to single notes, with the option to expand to intervals or triads? Things then become much more manageable, opening up possibilities for both chord inversions and soloing patterns. You may find it easiest to see the patterns by placing your fingers on the full chord for reference at first, but eventually this becomes unnecessary. In the examples, I’ve attempted to demonstrate a few practical ways of using the CAGED shapes as single-note patterns in combination with the pentatonic boxes.

It’s all about getting a different perspective on note groupings and breaking out of habits that can limit us. Finally, note that though I’ve occasionally quoted whole in the examples, the CAGED approach is often more subtle in everyday use. This example is undeniably shape 5 E major pentatonic, but try looking at it from the perspective of a G chord shape.

If you barre at the 9th fret (treating the barre as the nut) and add the G shape, you will get an E major – and see different possibilities. For example, in bar 3 I’ve deviated from the pentatonic pattern because I’m thinking about how I might embellish a G chord, rather than playing notes from a scale. I’ve chosen the D shape in the key of A major here.

First, I’m sliding up to those intervals that actually form part of the D shape, then playing around adding a sus4 and linking this with shapes 2 and 3 of the A major pentatonic. To reinforce what I’m trying to demonstrate here, I’ve returned to the D-shape A major chord. You’d probably want to do this more subtly in ‘real life’, but this is good stuff to know about.

Using the C shape, I’m doing little more than quoting B major and C major arpeggios here, reflecting the changing chords in the backing. If you look closely at these arpeggio/chord shapes and compare them to shape 3 of the major , you’ll see the shared notes. It’s unlikely we’d come up with note groupings like this if we were viewing things from a pentatonic or even three-note-per-string perspective.

We revert more to straight pentatonic to finish and give a more realistic context. Starting with an E major triad up at the 12th fret, things get a bit more pentatonic as this descends, only to quote an E chord shape directly as we ascend again. To finish, I’m getting back into a shape 5 E major pentatonic to demonstrate how these live in the same territory and how easy it is to switch from one to the other.

It’s not important to always be conscious of the shapes, as long as the ideas keep coming! This starts by quoting from the A shape that occurs at the intersection of shapes 4 and 5 of the E major pentatonic. Once again, I’m being particularly blatant about including the whole shape/triad in these examples, so don’t feel you need to do the same. This is about coming up with non-linear phrases, rather than quoting whole chords.

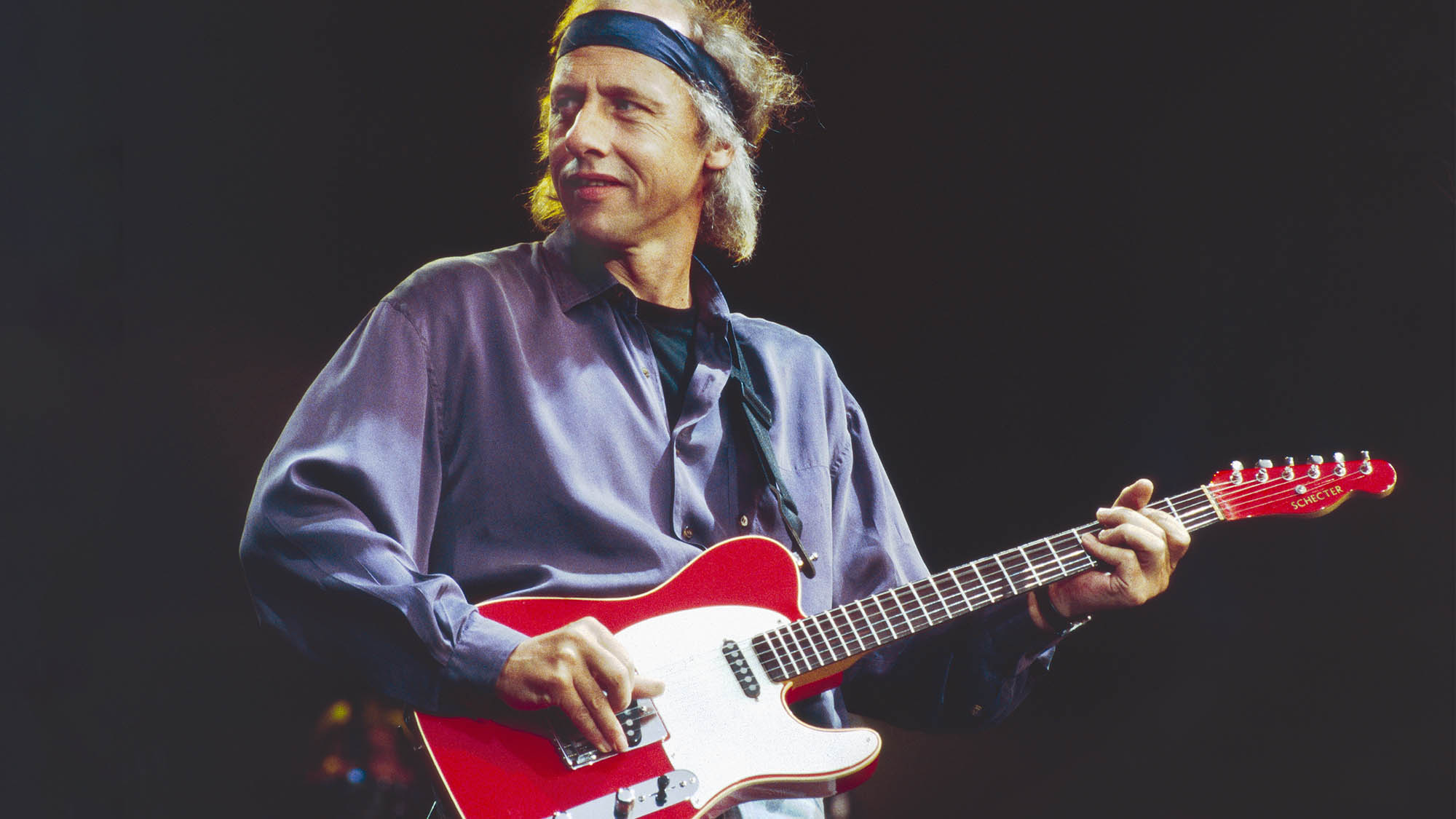

The intervals that slide down to the final lick are certainly chord fragments, too, but I’m seeing this more as a traditional blues lick. Mark is a master at combining the CAGED chord shapes with pentatonic lines as part of a rhythmic accompaniment or a melodic solo. On this compilation, check out how he moves the triads around in to create a melodic hook as well as a multitude of solo ideas.

takes a similar approach, using doublestops, chord fragments and melodic lines. Finally, check the main riff of Money For Nothing using a stripped-down D shape moved up to the key of G. Robben manages to combine pentatonic licks with chord tones, chromatic linking notes and triads in a natural, effortless-sounding way.

Check out , (where the licks that run through the whole tune are a nice example of using chord fragments) and with its blistering solo. You generally won’t hear arpeggios or chord shapes stated in an obvious way, but this is where these non-pentatonic ideas are coming from. Though Eric has taken the pentatonic scale to his own unique place, he has clearly absorbed every note ever played by Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck.

Check out his solos on the title track, plus and Camel’s to hear a combination of rapid-fire pentatonics, arpeggiated chords, superimposed triads and his unusual chord inversions with that super-clean tone. This is advanced stuff, but there are lots of accessible ideas to call on here..