Reading Danez Smith’s new collection, , I was reminded of a famous quotation: “I love America more than any other country in the world,” said James Baldwin, “and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” While Smith certainly (and aptly) criticizes the United States in , they also criticize other entities they arguably love: themself, the stars, poetry, their city. So much of seems to capture the wrung out feeling that is depressingly familiar to many.

It’s an emotion that leaves us teetering on the edge of becoming jaded, nihilistic even. The shapeshifting and incessant violences in the country (and world) are present in these poems, with Smith vacillating between a call to action (“if the cops kill me / don’t grab your pen / before you find / your matches.”) to impotence (“i don’t want america no more.

/ i want to be a citizen of something new.”) Like Baldwin, however, Smith is ultimately employing critique as an expression of love. For instance, the city of Minneapolis, where they live.

In , Smith describes Minneapolis as “my favorite place in the world.” (Smith was born and raised in St. Paul, and considers the twins of the Twin Cities ).

In , Smith interrogates the complications of their favorite place, including the creation of the I-94, which essentially destroyed the largest Black neighborhood of St. Paul’s . In another portion, they discuss in the wastewater of a St.

Paul suburb. When Chee asks Smith about being in Minneapolis during the unrest after the murder of George Floyd, Smith states, Those were very confusing, very illuminating, and very galvanizing times. You couldn’t not feel anything when things were on fire a few blocks away from you.

I was in the streets, but even if you were trying to stay at home, there were sirens, curfews, National Guard tanks marching down the street. It really interrupted the American currency of comfort. So, considering even the paradigm-shifting events within Smith’s community and what they imply about the larger country and world, it’s no surprise that “poems feel so small right now.

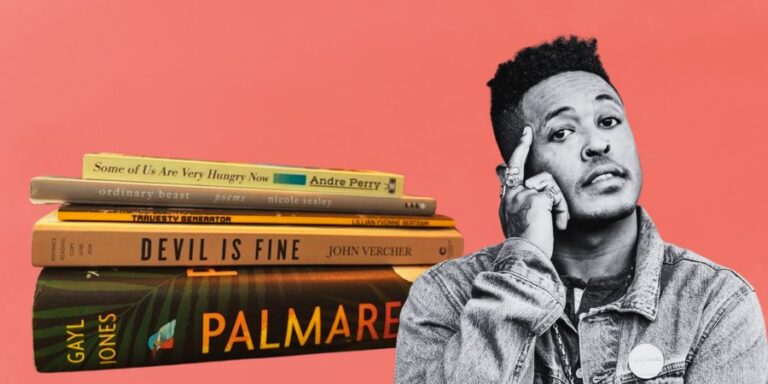

” And yet! And yet, they also illustrate the potential of our shared future. Because the future continues to come our way, that “means / there is still time / for beautiful, urgent change.” Describing their to-read pile, Smith tells us: “Teaching some poems, reading stories on my porch in the morning, and some genre-queer essays to top off the evenings.

” * “The variety of structures, formats, and rhythms Perry uses in is extraordinary,” . Perry writes beautifully about ugly events and feelings. He tackles racism head on and explores his role in fighting it.

He also recognizes how his drinking becomes a problem, a momentary escape that provides no lasting solutions. However, he can’t stop. Bars call to him.

Sundays, for him and his friends, are not a relaxing day; they are “the day when we choose not to rest but to continue chasing unfortunate outcomes and evading harsh truths.” These evasions and chases shape into a rough, heartfelt collection of essays that dig deep into who Perry is and engage the reader in the process with revelations that morph into mirrors that are uncomfortable to look at. Stephanie Burt writes in her brief review of at : ’s debut feels like a debut, in the best sense: a clever poet with a lot to say will try everything once, or more than once, in order to see what works, from centos, to poems that critique her own earlier poems (‘ ”’), to a sestina in which all six end-words are some form of “pit”—”Pity,” “pulpit,” “Eliot Spitzer”) to straightforward first-person reactions, as in one poem set in Nigeria: “The West in me wants the mansion / to last.

The African knows it cannot.” Sealey’s repertoire of devices might link her to , or to , whose tricky relation to memoir and to public trauma she also shares. Yet nobody will read Sealey for long without seeing her “thoughts turn to black people—/ the hysterical strength we must / possess to survive our very existence.

” Some of Sealey’s subjects are black America, gender in performance (a few poems pay homage to drag queens from the documentary ), love lost, and—in the final poem, an aubade—love kept and found. As a poetry editor at Noemi Press, the publisher of this National Book Award Semifinalist, I can only say: hooray! Bertram’s work is incredible, despite to their winning the last year (the tldr: their use of AI is not a cheat, but rather ). “Bertram uses open-source coding to generate haunting inquiring elegies to Trayvon Martin, and Eric Garner, and Emmett Till,” writes Cathy Park Hong in her blurb for By framing [their] ‘counter-narratives’ of black lives in code and social media optimization, Bertram brilliantly conveys how black experience becomes codified, homogenized, and branded for capitalist dissemination.

Code, written by white men, is part of the hardwired system of white supremacy, where structural violence begets itself. But Bertram hacks into it. [They] re-engineer language by synthesizing the lyric and coding script, taking the baton from Harryette Mullen and the Oulipians and dashing with it to late twenty-first century black futurity.

is genius. You can read a nice article on Bertram that delves into their use of tech in their work . In an interview with Malavika Praseed , Vercher explains his decision to employ second person in the novel: I never considered anything other than first person, but the second person arose out of a conversation with my editor.

First person was a challenge I wanted to take on, especially with an unnamed narrator. While you can argue that every narrator is unreliable, there’s something about the first person that completely hones you in on their view, and you have to take for granted what they tell you is true. Vercher goes on: But on the first draft, sending it to my editor, we detected a bit of narrative distance with the smartass, snarky narrator.

I couldn’t care less about an unlikeable character, but there has to be some level of relatability. So, he [my editor] brought up the idea of a confessional. That just sent all kinds of bells off in my head.

The minute I went back to the opening chapter and tried that, it made so much sense, it opened the book up in ways I never imagined. In a thoughtful, loving, yet fraught essay on Jones, a writer who was first edited by Toni Morrison in the 1970s, , The marvellous thing about the new novel, , is that Jones here allows women to get close without trying to destroy one another. Those feelings, however, still emerge under the dreadful cloud of oppression.

Set in seventeenth-century Brazil, the novel revolves around Almeyda, a Black slave girl, who lives on a plantation with her watchful mother and her caustic grandmother. Almeyda recounts her life in flashback..

.[she] has a story to tell, one that she has learned through quiet observation. “Look at Almeydita, how she’s watching with her ojos grandes,” someone says early on.

What Almeyda sees with those big eyes is colonialism at work. She is taught to read by a Franciscan priest named Father Tollinare, who is having an affair with Mexia, a half-Black, half-Indian woman, whom Almeyda is drawn to for her silences, just as she’s drawn to the words—the language—that Tollinare teaches her..