At the tail end of years of severe drought, farmers were putting up their farms for sale, seeking greener pastures. Once, the land had been in balance and the wildlife abundant. Herds of springbok took days to pass, and elephants and giraffes roamed the savannah.

The intense heat that builds up in the canyon walls chasing the clouds away did not affect the animals. They were adapted to the arid-zone conditions and migrated, following the scattered rainfall. Early indigenous hunter-gatherers, the San took only what they needed, and were followed by the Khoi pastoralists.

But the Western world was to stamp its heavy foot on the soil in the latter part of the eighteenth century. The repercussions would leave the land depleted and the perfect natural balance just a bright flash of ancient memory. EXTINCTION European explorers, hunters and traders crossed the Gariep (Orange) River into Great Namaqualand, hunting some species to extinction.

Trade routes radiated out from the Cape Colony and firearms and other Western commodities were traded for cattle and sheep. The Oorlams and groups originating from the Cape dominated local groups with their firearms, horses and raiding lifestyles. The combination of weapons and a swift means of transport enabled greater hunting efficiency.

Animal numbers plummeted in the south as the demand increased for items like ivory, ostrich feathers, klipspringer pelts for saddle blankets and long giraffe riempies (leather thongs), highly sought-after for ox wagons. Giraffes had disappeared by the 1830s and rhinos by the early 1800s. Waves of farmers battled the elements, the scarcity of water and the inevitable droughts, persevering through decades of political turmoil.

When German South West Africa was mandated to the Union of South Africa in 1919, South African farmers arrived, followed by another wave in the 1940s. Although the land edging the canyon receives significantly less rain than falls just a hundred kilometres east or north, early farmers mistakenly chose it for the promise offered by its open water systems, rather than for its proven grazing and carrying capacity. The farmers who arrived later on didn’t have the luxury of choice as the only farmland available was in the marginal rainfall areas on the edge of the Namib Desert and in the area bordering the Fish River Canyon.

INTENSIVE FARMING Intensive farming began in the middle of the twentieth century, made possible by the erection of government-subsidised buried-mesh fences, the drilling of boreholes and the installation of water pipes. This disrupted a productive grassland ecosystem and blocked the movement of wildlife, severely compromising their ability to survive. Instead of carrying a small number of sheep that were herded traditionally, following the grazing, as had been done previously by pastoralists, farmers were now able to build up their herds in camps.

The impact on the land was soon felt, exacerbated by drought and low rainfall. Farmers began to wage a war against the predators in the area with organised hunts and the use of poisons like arsenic and strychnine. This affected all scavengers and small predators in the area, such as genets, foxes and aardwolf and especially the avian kind – eagles and vultures.

The loss of these species and their role in controlling the insect, reptile and rodent populations further disrupted the ecosystem. After the lucrative karakul pelt market crashed, a long drought ravaged the land from the mid-80s until the early 90s, stubbornly persistent like an unwelcome guest. Desperate farmers began to sell off their barren land and move to the towns.

A few stayed on, some shooting out the remaining wildlife for short-term gain. By the time we bought the first farm bordering the eastern section of the Fish River Canyon, the cycle of landowners had run its course; it was evident that intensive farming practices were not sustainable in the long-term. ECOTOURISM They understood that the only sustainable form of land use with the potential to level the environmental scales, restore the wildlife and vegetation, and be able to nurture the land, would be ecotourism.

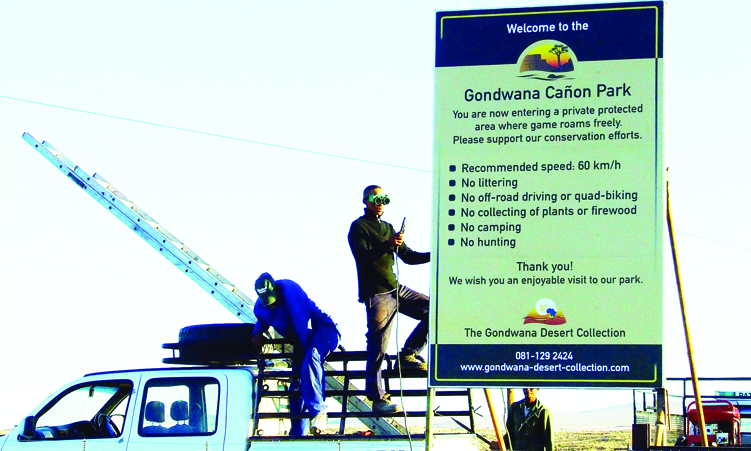

This would ultimately fund the larger conservation area. Realising that it was not a vision that could be sustained by just a few people, other like-minded investors with environmentally sound philosophies were sought. The vision matured over the subsequent 15 years as the group of lodges called the Gondwana Collection Namibia was born, and the concept of a large, protected area was developed.

Over the years, a further 10 adjoining farms were acquired in the area bordering the Fish River Canyon. Fences were dismantled and relics of sheep-farming removed. Research was carried out to establish which animals once historically occurred in the area and new stock of red hartebeest, wildebeest, plains zebra and giraffe was gradually reintroduced.

The Gondwana Canyon Park expanded to encompass an enormous area of 130 000ha (1 300 square kilometres). It is now one of largest professionally run privately protected areas in Africa with highly qualified park wardens and rangers and formal, structured management activities. These include a yearly game count, regular natural resource monitoring and cataloguing of park biodiversity, water installation management, research and training, alien species control, anti-poaching patrols and frontier fence management.

The land responded well to the new balance, although drought years still bring hardship and suffering. Flora has regenerated over the years and the fauna has increased as the animals are once again able to follow the scattered rainfall prevalent in the area, not restricted by fences. As the greater area is restocked and restored, there is a ripple effect of life-affirming positivity.

The sounds of the wild can once again be heard..