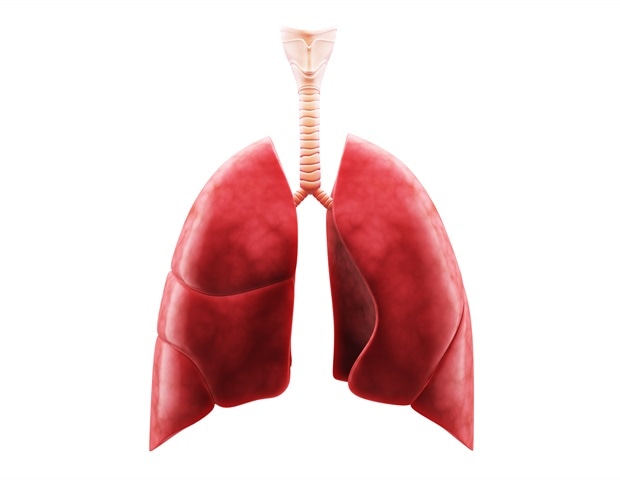

With each breath, a human may inhale thousands of harmful microbes into the lungs. Mucus, the gel-like moist substance coating the airways, is one of the first lines of defense and aids in removal these microbes. It entraps bacteria, viruses, dust and pollen to protect the lungs, and the mucus is moved up and out of the airways by the beating of tiny hair-like projections called cilia.

But what happens when the body produces too much mucus that is too thick, viscous and dehydrated to move and clear properly? Overly thick and sticky mucus over time can obstruct the airway, overwhelming mucus clearance mechanisms, resulting in a breeding ground for entrapped microbes. These pathophysiological processes contribute to the development of muco-obstructive diseases including cystic fibrosis, or CF. A research team at the University of Alabama at Birmingham led by Jarrod W.

Barnes, Ph.D., an associate professor in the UAB Department of Medicine, and Steven M.

Rowe, M.D., a professor in the UAB Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, has investigated defective mucus formation.

They show in the journal Scientific Reports how a single sugar modification on mucus affects its expansion and transport. Mucus is a hydrogel composed primarily of water and solid matter, including large sugar-coated protein molecules called mucins, the principal component of mucus. The research focused on the addition and removal of a terminal negatively charged sugar m.