I once heard American author William Faulkner speak to a small gathering of French students, teachers and college people. After the talk, someone asked Faulkner if American students think. It seems a curious question, but a decade after World War II, France was still recovering from defeat and the German occupation, and had a sort of national inferiority complex, and consoled itself with the idea that although America was more powerful, France represented a superior intellectual culture: They were Greeks to our Romans.

Faulkner answered by saying that thought, in an American youngster, was a product like sweat: It occurred under stress and was not normally called forth. The talk moderator was appalled and tried to walk back Faulkner's reply, but Faulkner stuck to his position, and the audience went on to other questions. Of course Americans think, I told myself, every day, on the job, problem-solving, figuring out how to make more money for the firm.

However, the lectures and bull sessions of college are a distant memory; maybe philosophical thinking was what the questioner meant? Napoleon saw the problem when in the early 1800s he established the public high school (lycée) system: All French secondary students — academic and vocational — are required to take a course in philosophy in which they are expected to write answers to questions like the following: ■ Can a scientific truth be dangerous? ■ Is it one's own responsibility to find happiness? ■ Is observation sufficient for knowledge? ■ Can the faculty of reason give the reason for everything? ■ Is a work of art necessarily beautiful? ■ Am I what my past has made of me? ■ Is respecting all living beings a moral duty? ■ Is politics free from a requirement of truthfulness? The students have four hours to answer one question, or they can analyze a passage taken from a canonical philosophical text. Most choose the question. They are advised to take two hours to construct an outline, and the remainder to writing and polishing the final draft.

The students dread this exercise. The failure rate is high, though a low grade here can be compensated by success on the other parts of the weeklong exam, called the bac (for baccalaureate), which 90% of students pass. French grades are based on 20, with 10 the minimum passing grade.

20s are almost never awarded, and a typical failure score is seven. Nevertheless, the bac is not the drama it was two generations ago, when about a third of students failed, and their mothers picketed the schools. (The fathers were at work.

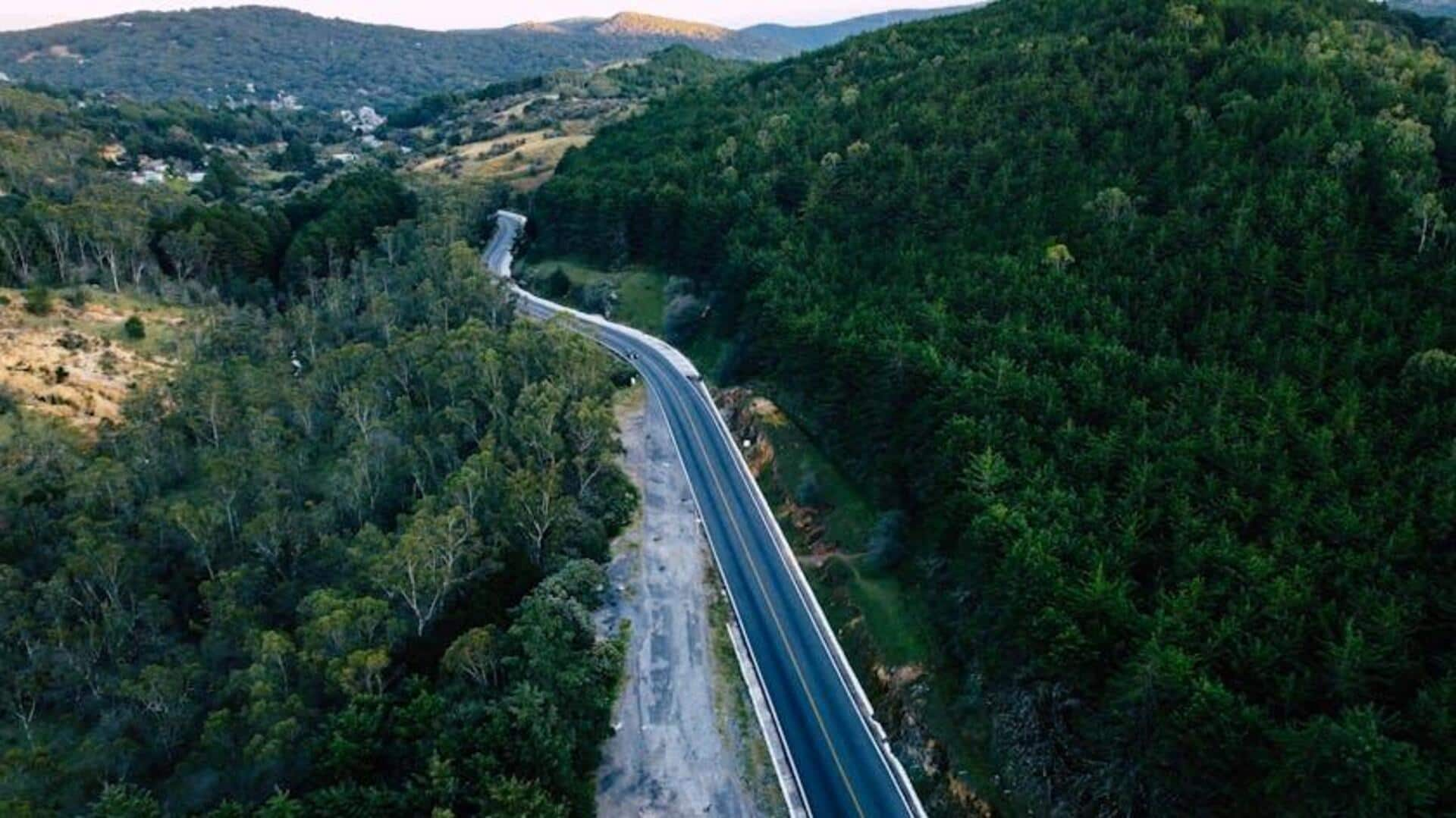

) Success on the essay, or dissertation, comes from producing a text carefully reasoned from point to point, like a path surveyed across a wilderness. Appeals to experience, or "what one knows," or feels, or ideas "in the air," are discouraged. The dissertations often take the form of thesis, antithesis, synthesis.

There are no right or wrong answers, and the conclusion is not as important as the reasoning that leads up to it. It seems like a lot to demand of 17and 18-year-olds, but nobody seems to worry about damaging students' self-esteem. To think clearly, logically and consistently is thought to be the underpinning of a democratic state, which the most recent French republics have been in different ways.

The current exam may seem repressive, discouraging self-expression, but the reasoned path is thought to be a "Road to Freedom," as Jean-Paul Sartre put it. Critics see it as a tool of class: The best way to succeed at the bac to have parents who succeeded, they claim. They call the exercise "thèse, antithèse, foutaise (bulls—-)!" In France, exams are a cult.

The successful man (or woman) is the one who passes exams brilliantly, especially in one of the grandes écoles (graduate schools). Unfortunately, the brilliant passers of exams — some have been called prissy — display arrogance and a too-theoretical approach to problem-solving. In France, the executive with the right diplomas enjoys more prestige than the hardscrabble business tycoon who has fought his/her way up without much formal education.

So, do the French think? I think yes, most should have at least a basic grasp of logic; but on the other hand, my French friend Bernard, an Alsatian, when we were talking one day in Lyon about politics, at one point looked at me incredulously and asked, "Do you really believe that people here think?" and rolled his eyes. ed Rossmann lives in aurora and has been an educator most of his life, including 17 years in high school. Get local news delivered to your inbox!.