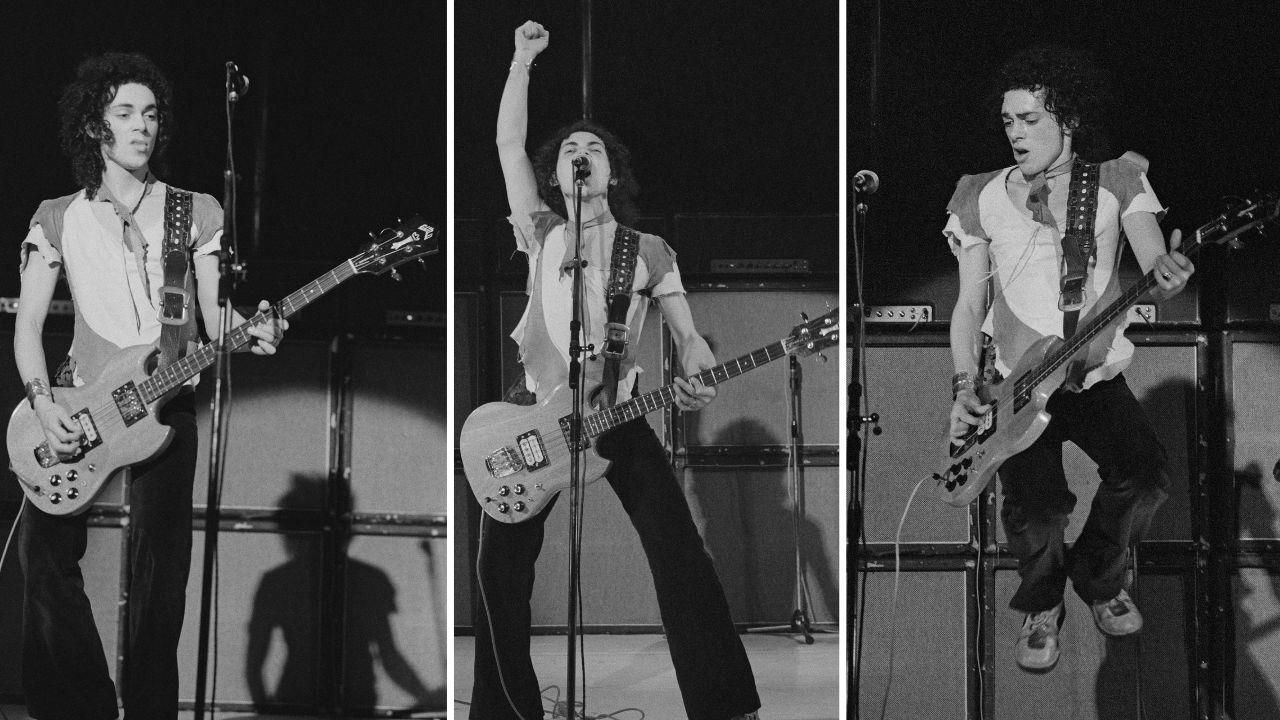

There's a saying that holds some weight: if you're good enough, you're old enough. While it's certainly true that most rock stars achieve their breakthrough in the relatively inexperienced years of their early to mid-20s, not so many manage it while still a teenager. After a brief tenure with John Mayall at just 15, Andy Fraser joined what would become the iconic rock band Free.

Fraser was the youngest member of a group in which no-one had reached 20, and although the band's albums initially sold modestly, they exploded into worldwide fame with the success of , driven by the Fraser co-written dad-rock staple . In many ways that song is a microcosm of why Fraser, who died in 2015 aged 62, was such a wonderful bassist: that tight, punchy groove in the chorus, the funky line at the low-end in the guitar solo that acts as a call to the answering melodic figure played higher up the neck – and, most shocking of all, the total absence of any in the verse! And yet Fraser could certainly busy it up when he wanted to, as evidenced by his vamping line during the instrumental section of “People have long talked to me about the impact that solo had on them,” said Fraser. “But I really never gave it a lot of thought.

Truthfully, I don't even think about the bass. I work on the overall sound, and when a song needs bass, I get it out and play what's natural. With keyboards, you can hear all the luxurious harmonies, but with single bass notes, you've got to be very creative in your phrasing to make the chord changes obvious.

” After guitarist Paul Kossoff's short, legato solo, Fraser ramps up his two-minute at 3:06 with a string of staccato lines, working his way into the upper registers with gospel-shout-type chromatic runs. In 2005, thirty-five years after his staid groove helped anchor , Fraser released , his first solo album in over 20 years. The cathartic , with its African rhythms and other world music flavors, was a heartfelt document of the post-Free years Fraser spent overcoming his battles with depression, cancer, and AIDS, while struggling to come to terms with his homosexuality.

The following interview with took place in November 2005. “I was the diplomat who became a bass player because everybody else wanted to play something else. But it came to me quite easily; I found I could listen to Stax and Motown records one or two times and be able to play the .

” “When I was about 13, I started playing in all-night East London clubs with much older musicians. Looking back, it was probably highly illegal for me to be playing in clubs at that age – these places were just getting started at 2am! But it gave me a lot of firsthand experience playing RSB, blues, ska, and soul.” “I generally listen to the vocal and try to supplement it – if there aren't vocals, there's no need for bass.

Robert Palmer once played me a track and asked me to add some bass. I said, ‘Robert, there are no vocals. I have no idea what to do.

’ I made him put the vocals on there so I had something to play against.” “Well, that's probably one of the reasons I've driven so many drummers nuts in the past! Having programmed the drums on , however, I've become more acutely aware of making the kick drum and bass work together. But it's still easier for me to play bass first and then add the kick.

I find that if you do what's obvious for the drums, it just doesn't work for the bass.” “It did in the Free days, when my only means of expression was the bass. Nowadays, I have control over all the elements.

So much more can be expressed vocally and lyrically.”.