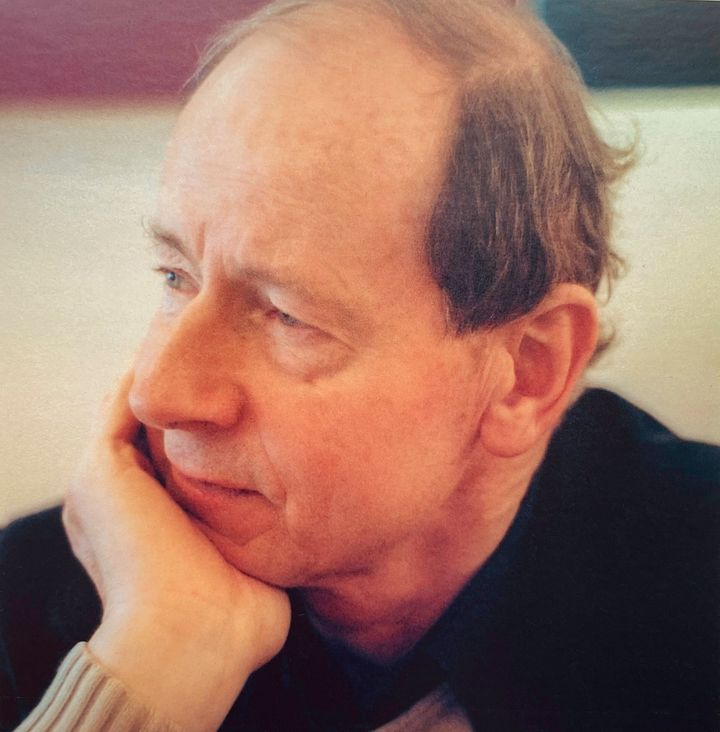

Hugh Bredin also taught voluntarily at Long Kesh Hugh Bredin, who has died aged 85, was a senior lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast (QUB) in scholastic philosophy and will be remembered for his prolific writing, strong social conscience, his diverse range of interests and his commitment to his students. Such was his political awareness, he was one of a number of academics who publicly opposed internment without trial in the North during the Troubles and he taught prisoners in Long Kesh on a voluntary basis. A lifelong friend of Seamus Heaney from schooldays, he had a keen interest in poetry, art and literature.

He had a facility for languages and translated writings on medieval aesthetics by Umberto Eco, the Italian philosopher, novelist and cultural critic. Hugh Terence Bredin was born in Coleraine, Co Derry, in April 1939 and grew up in Maghera, where his parents were primary school teachers. He attended secondary school at St Columb’s College in Derry, where Heaney was one of his classmates.

Later Bredin registered to study for the priesthood in Maynooth University, but took a degree in English instead as he was said to have been disillusioned with the regimentation and potential boredom of a church vocation. He became a school teacher and taught from 1961 to 1964 before opting to register for a master’s degree in philosophy at QUB. He credited the university’s professor of philosophy Theodore Crowley for encouraging him to pursue an academic career.

Bredin shared an apartment with Heaney during his early postgraduate years and secured a PhD in philosophy in 1967. During the 1960s, he was a member of “The Group”, a creative writing and discussion forum initiated by poet and critic Philip Hobsbaum who was then lecturing in the arts faculty at QUB. Members included James Simmons, Stewart Parker, Bernard MacLaverty, Michael Longley and Seamus Heaney.

He was appointed as assistant lecturer at QUB in 1966 and became senior lecturer in 1974. He took a keen interest in the writings and work of Noam Chomsky during a year as a visiting fellow at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where the US linguistic expert and social critic worked as a professor. Bredin’s linguistic ability meant that he could teach himself a new language wherever he was for research purposes.

This skill extended to music. While a student at Maynooth University, he taught himself to play cello for a one-off performance and he maintained an interest in music, particularly piano, throughout his life. During his 39 years at QUB, he held administrative and committee roles, with much committee work reflecting his interest in student welfare.

He supervised a number of postgraduate students, including journalist and writer Fionola Meredith, who said that she “valued his exceptional clarity of thought and his ability to express and explain complex philosophical ideas in language of great eloquence and simplicity”. We are all empirically aware of the brutalising effects of ugly surroundings on the people who live in them Among the many students he influenced was Kieran Conway, a republican prisoner in Long Kesh when Bredin taught voluntarily there in the 1970s. Writing in Southside Provisional: From Freedom Fighter To The Four Courts , Conway, who became a lawyer, credits Bredin’s influence and says Bredin “brought an entirely new dimension to my thinking”.

Bredin was co-author with Liberato Santoro-Brienza of the seminal work, Philosophies Of Art And Beauty: Introducing Aesthetics , published by Edinburgh University Press in 2000. He contributed many papers to academic journals on subjects ranging from art and literature in Plato’s Republic to the semantic structure of verbal irony. In his paper on the theory of beauty, which his widow Isabel quoted from at his funeral, Bredin wrote that “we are all empirically aware of the brutalising effects of ugly surroundings on the people who live in them, and a partial measure of the nobility and wealth of a culture is its concern for beauty and its capacity to create and enjoy it”.

He wrote a piece on censorship for the Newman Review in 1969, which, in the opinion of his son, Lurach, reflects how his “philosophical and cultural views were connected to the world in which he lived, with the lived experience of people and cultures, as opposed to the more formalist and abstract tendencies in philosophy and culture”. An evil in itself, it is a perversion of law and infringes the most fundamental human right of all: freedom Bredin was also a signatory to a statement opposing the policy of internment without trial introduced by the British government in the early 1970s in Northern Ireland. The signatories described internment as “an evil in itself, because it is a perversion of law and because it infringes the most fundamental human right of all, the right to freedom”.

He sent more than 50 copies of the statement to various diplomats and politicians, and his extensive library includes replies from the late former taoiseach Garret FitzGerald and Conor Cruise O’Brien. Bredin married Noelle Agnew, daughter of mid-Ulster Irish republican lawyer and activist Kevin Agnew, and the couple had three children. They later divorced and he married Isabel Kangas in 1983 and the couple had two children together.

Bredin undertook literary reviews, wrote regular reviews of poetry for Fortnight magazine, and wrote a short story, The White Flower , about a clerical student fed up with church management. It appeared in Modern Irish Love Stories , edited by David Marcus and published in 1974. Towards the end of his academic career, he railed against QUB managerial forces which were proposing cutbacks in key humanities departments.

Having always been interested in Chomsky, he took his “political gadfly” approach to the issue, editing and writing anonymously on the impact of such evisceration of the arts and humanities for a satirical magazine, Barbarus . In a letter to The Irish Times in July 2002 on the closure of the school of classics in QUB, he responded to a fellow academic’s statement that the study of classical texts in their original language would continue in Queen’s, even though the languages in which the texts were written would no longer be taught. “This is rather like saying that physics will be taught at Queen’s even though mathematics won’t.

Or that palaeoecology will be taught without students having to learn about carbon dating,” Bredin wrote. Bredin’s connection with Italy and with North America was abiding for much of his life — in addition to “a broad interest in the wider world, and a deep and multi-faceted connection to the culture of Ireland”, his son Lurach said. At his funeral, celebrant Brett Lockhart recalled how Bredin was part of a notable generation who taught scholastic philosophy at QUB, alongside colleagues such as his close friend Tim Lynch and Jimmy McAvoy.

Bredin exemplified what the 19th century theologian and priest Saint John Henry Newman envisaged in his The Idea Of A University : to “think and to reason and to compare and to discriminate and to analyse”, Lockhart said. For all his erudition and academic sophistication, Lockhart said, he also had a strong faith which was “straightforward, uncomplicated and unwavering”. When Bredin was diagnosed with dementia, he felt the assault on his mind which had been “such a forensic instrument” very deeply.

Lockhart said the insight of Dylan Thomas resonated with his family, when the poet wrote: Do not go gentle into that good night, / Old age should burn and rave at close of day; / Rage, rage against the dying of the light . Bredin's cousin, journalist and author Deaglan de Breadun, gave a reading at the funeral ceremony. Hugh Bredin is survived by his wife, Isabel, and his children Susannah, James, Lurach, Michael and Anne.

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel Stay up to date with all the latest news.