My daughter has anxiety and left school with two GCSEs...

it's only now I realise my parenting style is responsible By Anonymous Published: 01:52, 23 August 2024 | Updated: 01:57, 23 August 2024 e-mail View comments The other day, I asked my 17-year-old daughter, languishing in a fug of summer boredom, what she wanted to do with her life. 'I want to be a stay-at-home mother,' she replied. My eyes nearly popped out of my head.

'Why? Don't you want to get a good job and be independent?' I blurted, and then launched into a speech about how women had fought hard to enter the workplace on a level playing field with men. Her reply, however, silenced me. 'It's because I don't want to be like you,' she said.

'I see you working too hard and you are exhausted and you're always complaining about money, so I really don't know why you do it. I just don't want to be you.' Ouch! She went on to tell me that my anxiety about her future makes her feel anxious herself.

That I am too often hovering over her, attempting to sort her life out so that it fits my idea of a successful one. 'Why can't you trust me to do it myself?' she said. In some lucky families, this would be nothing more than an isolated outburst.

The letting off of teenage steam. But in mine, it was especially pointed, for my daughter does in fact suffer from anxiety, for which she is in therapy. She has long been a school refuser and left school last year with just two GCSEs.

This might be very pertinent for people who have children who received their GCSE results yesterday. My daughter got her results 12 months ago and, while I would like to say I was relaxed about it, I very much wasn't. I kept telling her I was 'chilled', but I was riven with anxiety about whether she would get any exams at all and what she would do afterwards.

Like many women of my generation, I admit I have a tendency to over-parent – and always have done. Despite my best intentions to let my daughter manage her own life and empower her in order to do that, I have a horrible suspicion that my daughter's right and that – as though in some nightmarish vicious circle – my anxiety has made her anxious and this is why she has become too ill for school. Perhaps the correlation between my hands-on parenting and her anxiety isn't confined to just us – perhaps we helicopter mums are partly to blame for society's anxiety epidemic.

There's no question the number of young people suffering from anxiety is far higher than it used to be. A whopping 89 per cent of 18-24 year olds told the Mental Health Foundation in a recent survey that anxiety 'interfered with their day-to-day lives to some extent'. Another study published in the British Journal of Psychiatry found that diagnoses of anxiety had tripled in young adults since 2008.

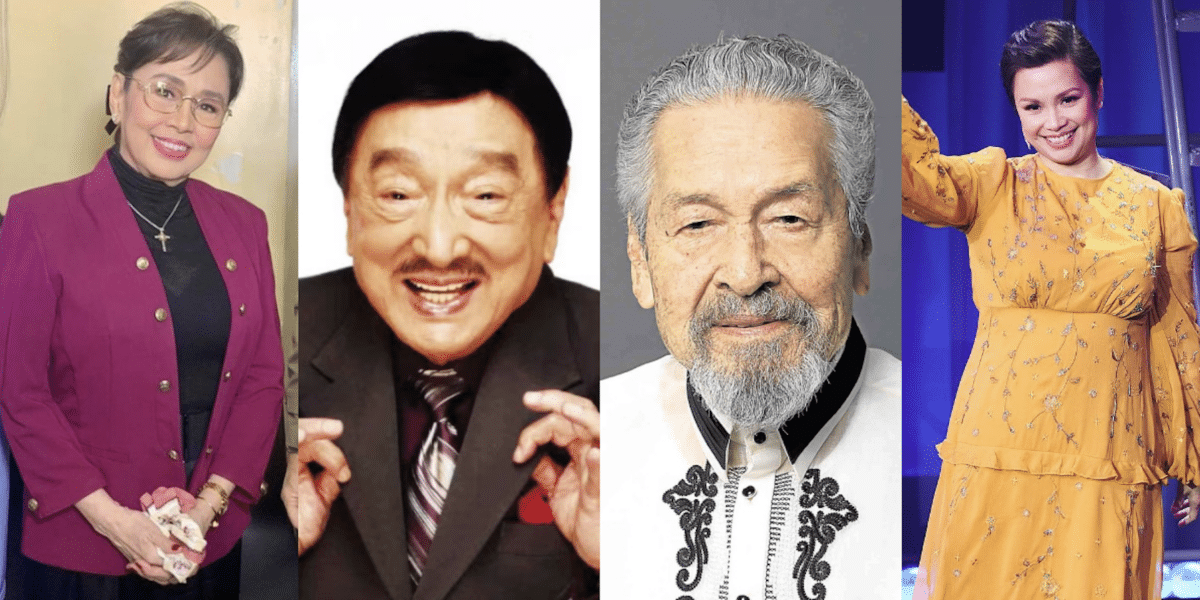

Figures from NHS England suggest one in five young people aged eight to 25 had a 'probable mental disorder', including eating disorders and anxiety, in 2023. My daughter told me that my anxiety about her future makes her feel anxious herself (Picture posed by models) She has long been a school refuser and left school last year with just two GCSEs (Picture posed by a model) My daughter is very much part of this cohort. She was diagnosed with dyslexia aged ten and her anxiety around conventional academic lessons at school meant, after the pandemic, she started refusing to go.

She would attend school for a bit but, gradually, she went less and less. Then, one day, she just flatly refused to go. She said she felt too anxious, too upset, too overwhelmed.

And when last year she passed just two GCSEs, I did what I thought any good, modern, helicopter mother would do and took her choices in hand for her. I found lots of vocational courses she could do – animal management, health and beauty, childcare, travel and tourism – and applied on her behalf to colleges for every one of them. Then I put all my research and applications together in a ring-bound folder, and highlighted all the important information I thought she needed to know.

I was incredibly proud of myself. And yet when I gave her the folder a nanosecond after she received her results, she looked at me in a way that made my blood run cold. 'Why did you have to do this?' she said.

I blathered on about the next few years being critical and the things I thought she enjoyed – and then I realised something with an absolute clarity: this was about my anxiety and not her future. I hadn't even asked her what she wanted to do. My smug ring binder was a result not only of concern and love but also of panic.

I did something similar to my son. Now 20, he came out in physical hives while sitting his exams. I come from a highly academic family, and my siblings and I sought praise from our parents by outperforming each other in terms of how clever we were.

My entire family went to top-notch universities, and I fully expected my poor son – who is perfectly clever but not Oxbridge material – to follow the rest of us. And so I pushed him, pretty relentlessly, down that path, not realising, or even stopping to think, that his laidback, outdoorsy nature meant studying law in a dry library at a Russell Group university was his idea of hell. For months of that law course, he told me later, he barely slept.

He desperately wanted to drop out and re-train – his dream was to become a tree surgeon – but he couldn't face my reaction. He feared making me anxious about his future. How topsy-turvy is it when our children make themselves unhappy in the service of our mental health? I was their role model and what I was modelling was overwhelming anxiety – about them, about money, about life.

Yes, I overwork. But that's because, as a single parent, I'm worried that the money will run out. I spend most of my days in financial anxiety because I am convinced that, unless I work 24/7, I will not be able to pay the bills and then what will happen? I feel a huge amount of guilt surrounding the breakdown of my marriage with their father.

My daughter was only four at the time and, deep down, I have a belief that her life went into freefall after he left. I constantly berate myself. I tell myself that if I had tried harder and he had tried harder, my daughter would be a fully-functioning person who got a clutch of 9s at GCSE, and will next year happily sit A-levels.

I did what I thought any helicopter mother would do and took her choices in hand for her, finding lots of courses she could do and applying on her behalf (Picture posed by models) Despite my best intentions to let my daughter manage her own life and empower her in order to do that, I have a suspicion that my anxiety has indeed made her anxious (Picture posed by models) I also feel guilty because I was a working mother when they were young and, although I tried my hardest to get to nativities and show-and-tells, and manage outfits for World Book Day, I was rarely at the school gates. I did have people who deputised for me – my mother and a pretty wonderful au pair – but I remember my daughter's plaintive little voice one day saying to me 'Why do you never pick me up from school?' and the guilt descending like a ton of bricks. I had so much to do all the time, I was always worried I wouldn't do it properly.

Not just shopping and laundry and making dental appointments, but managing screen time, friendship issues, childhood illnesses; all on top of the work I do to pay the bills. We all want our children to be happy, to find a lovely partner and a fulfilling, lucrative job, to build a successful life. But when they look at us, perhaps all they see is how impossibly hard that is.

I think this is why we constantly try to smooth the way for them. It's almost as if we can't help it. In my eyes, the future my daughter sees for herself – a quiet life, building a family – isn't good enough for her.

I can feel the tension rise in my body when I think about it. We see the world as a tougher place than when we were growing up and we constantly step in to 'make it better' for them, yet this very nervous, overly tight bond we have with our children in the end simply stops them from growing. If we treat them as if they can't cope, they won't cope.

I wonder if it is a reaction to the hands-off parenting my generation experienced. Maybe we all felt we were under-parented and not prioritised, and we've reacted by going too far in the opposite direction. I don't think our parents really knew how to parent in a hands-on way because their parents didn't do that.

I don't think it ever occurred to them that they should be overly involved in our lives. When I was a child it would never have occurred to me that I could refuse to go to school. Even if I was ill, I was marched off to get on the bus.

I don't think any of us particularly enjoyed our childhoods or thought we had any autonomy whatsoever. This is probably why we have gone the other way and now over-parent. We are all about feelings these days, and not dismissing 'lived experience', whereas in the past children were told to 'suck it up' if they expressed anxiety or to 'be brave'.

Read More High school teacher reveals why it is essential for parents to let kids FAIL if they want them to be high achievers - and warns hiring a tutor could turn them into 'stressed-out perfectionists' At best, our mums might have realised we were worried about exams or the size of our body, but their general approach was not to talk about it in case it made it worse. 'It's just a phase', 'Chin up', 'It'll seem better in the morning' were the stock phrases trotted out if we ever expressed a hint of worry. In fact, I was verging on anorexic as a young teenager.

I used to slip food from my dinner plate into my pockets and throw it out of my bedroom window later. I look back at photographs now and see how painfully thin I was. Recently, I asked my mother what she thought was going on as I got increasingly thinner and she said: 'I thought it was better not to talk about it.

I hoped you'd just get over it.' In my mother's generation, they believed that sweeping everything under the carpet worked, the theory being that if you didn't see your parents were anxious about something then there was no need for you to be anxious about it either. While no one would advocate ignoring the signs of an eating disorder, there is something to be said for not exposing children to our own anxiety.

It is the parents' job to shoulder the burdens of the family without falling apart, after all. If our children have problems and issues, we must listen to them but not treat it like the end of the world. And not step in with ring binders either.

If we model to children that being anxious is a normal state of affairs, we are bringing up children who are prone to anxiety. We are showing them we don't trust them and we don't trust the world and we don't even really trust ourselves. As my daughter once said to me: 'I may get it wrong, Mum, but that's how I learn.

' Her wisdom on this should be reassuring. If we want to solve the anxiety epidemic plaguing our teens, we must resist the temptation to fix the world for them. And, for Heaven's sake, chill out ourselves – especially if those GCSE results don't go according to (our) plan.

World Book Day GCSE Share or comment on this article: My daughter has anxiety and left school with two GCSEs...

it's only now I realise my parenting style is responsible e-mail Add comment.