Ashley Dedmon’s parents always told her knowledge is power. Discussions about health, she says, were the norm growing up. “They were educators,” Dedmon says of her parents.

“They were always wanting my brother and (me) to have all the knowledge that we needed.” And so, they stressed openness about family medical history. It’s a practice that’s long given Dedmon the courage to advocate for herself in medical spaces, where .

Because she knew the illnesses that were prevalent in her family, Dedmon underwent genetic testing to assess her risk for disease at 21 years old. She tested positive for the , which increases the risk for breast, ovarian and other types of cancers, per the . And this set Dedmon on a health journey she'll likely be on for the rest of life.

Now 38, Dedmon and her husband have maintained the same practice as her parents when it comes their two daughters. They stress the importance of their girls monitoring their bodies. Recognizing changes in themselves, Dedmon tells TODAY.

com, is vital. They know the difference between signs, something you can see, and symptoms, “something that mommy and daddy may not be able to see, but you can feel.” “I’m empowering them to talk about their own personal history and sharing that information not only with us, but even when we take them to the doctor,” Dedmon explains.

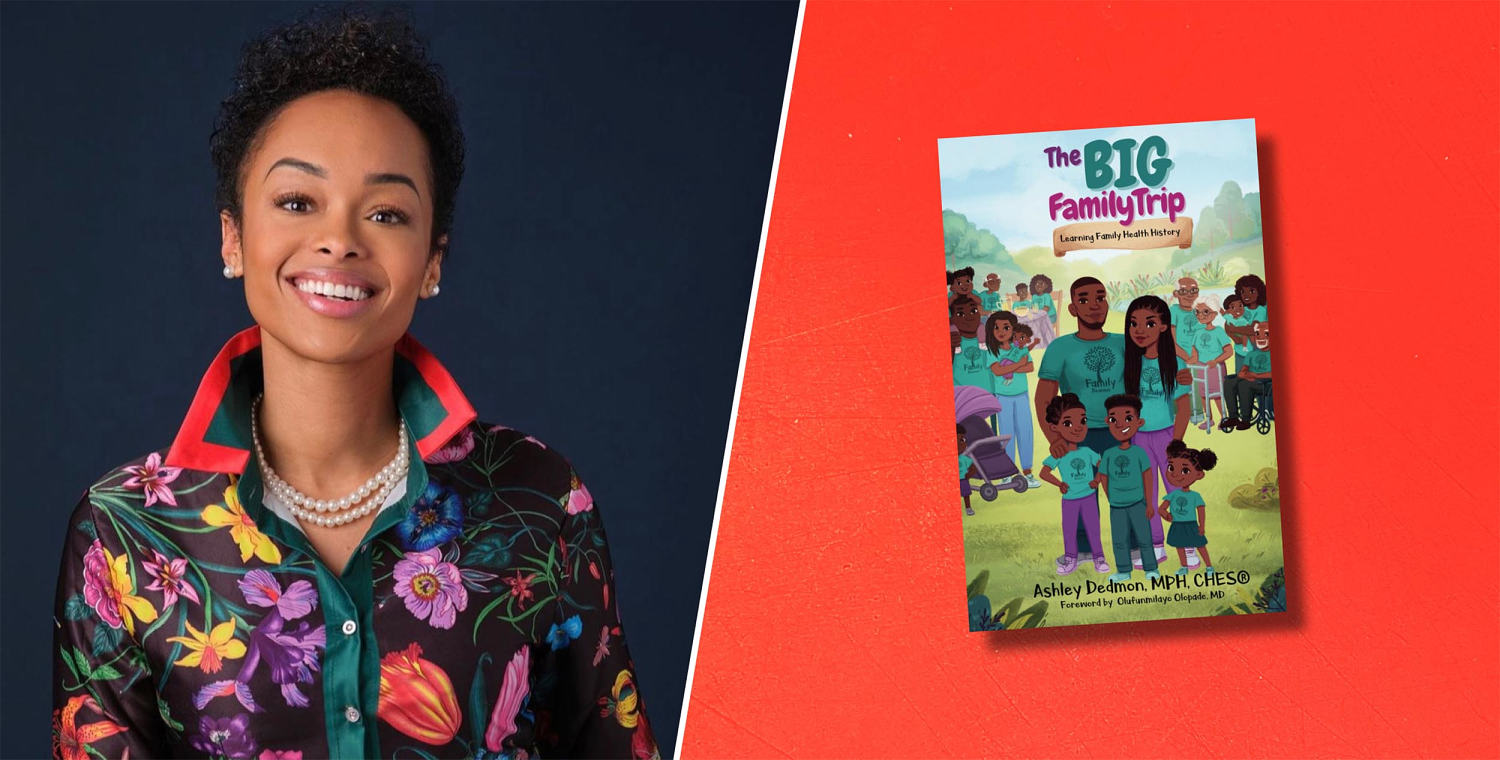

Self-advocacy, Dedmon adds, gives children agency over their bodies and their futures. This way, down the line, they’ll have the courage to share it with those who need the information most — their own families. This is precisely what Dedmon’s most recent children’s book aims to tell readers.

“ ,” offers guidelines to kickstart and then navigate conversations with loved ones about their health early on. In 2003, Dedmon’s mom tripped and fell. When she went to have her subsequent back pain examined, doctors told her she had stage 4 metastatic breast cancer — the very disease Dedmon’s grandmother and great-great grandmother also had.

Dedmon’s mother received treatment at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where she had hormone therapy, chemotherapy, radiation, "and I believe she was also offered a clinical trial,” says Dedmon. After a few years of treatment, her mother died in 2007. Then, just as Dedmon was preparing to graduate from university she got a call from her father.

He’d been diagnosed with prostate cancer. “I was at the library,” says Dedmon. She remembers the fear that washed over her body.

“I was scared for my life.” She didn’t want to be next. So, she brought this information to her own doctors.

Dedmon credits the conversations with her parents and her role as their caregiver for instilling the drive to look after her own health. “Going with them to their visits, their appointments, different screenings and scans and treatments really put me in a position to learn — learn how to interact and engage with persons in the health care system,” Dedmon says. When she felt compelled to investigate her own health, she knew exactly what to do.

She started first with her OB-GYN, the same physician who treated her mother, who connected Dedmon with a high-risk oncologist, who began monitoring Dedmon’s breast and ovarian health. The tests the oncologist ran showed Dedmon was positive for the BRCA2 gene mutation. “That was the beginning of my risk management, knowing that I am a carrier,” explains Dedmon.

Next, she assessed her options, which included hormone therapy, early initiation to screening, and prophylactic or preventative procedures. “And after exploring all of these options, the early initiation to screening was the best route for me,” she said. Then began Dedmon’s regular mammograms, breast MRIs, breast ultrasounds and, eventually, a preventative double mastectomy.

Dedmon had an intimate knowledge of her body and her risk. “One, I’m a Black woman,” says Dedmon. Black women have the lowest survival rate for breast cancer, according to the .

And while the incidence rate of breast cancer is higher in white women, Black women have a 40% higher breast cancer death rate. It’s also the leading cause of cancer death for Black and Hispanic women. “Two, I had dense breasts.

” Women with dense breasts are more likely to have breast cancer, per the . And dense breast tissue can make it difficult to detect cancer in a mammogram. “Three, I had family history.

Four, I’m a BRCA2 mutation carrier. With all those factors,” Dedmon says, “I knew my risks were, without a doubt, higher than the average woman." Dedmon’s own experiences with her family, her work as a teacher, and parenthood inspired her to write “The Big Family Trip,” her second book.

“'The Big Family Trip' is focused on and promotes open discussions about family health history, to empower families to make informed health decisions and to share that information with their health care providers,” says Dedmon. “When we know our family health history and we share that with our doctors, it can help identify any type of lifestyle changes that we may need to make. It can provide our doctors with recommendations for treatment or any other options that we may need to reduce our risk.

” The book, about a family reunion where elders recount their life stories, including medical history, is resource for how to stay informed and how to show up for your family by sharing your own story. Dedmon is careful not bring on worry, as she careful not to do with her own children. Since her youngest is just 2 years old, Dedmon hasn't given them all of the details about her family's medical history.

She knows it can be complex and scary, so she's eased them in by encouraging interest in their personal health. Her oldest daughter, however, is aware of the family's history of cancer and knows about Dedmon's BRCA2 mutation. Right now, Dedmon's aim is to empower them and help her children to speak up for themselves at their doctors’ appointments.

“We always put them in the seat closest to the doctor,” says Dedmon. “And I always have the doctor refer their questions ..

. to them.” She and her husband will fill in the blanks when necessary.

Her goal is to normalize conversations about their health so that they can advocate for themselves when they’re older and can better understand their family's health history. Of course, says Dedmon, not everyone has access to family medical history because of adoption or estrangement. “But family health history can start with you,” says Dedmon.

Dedmon chose to feature a Black family in her book because of the health care disparities that predominately impact Black people, limit health literacy and create a gap that often leaves Black families behind. “I really wanted to create a resource that features Black characters and reflects our identities as a culture and addresses health topics relevant to our community so we can empower and engage in those health conversations in a confident way,” says Dedmon. “We are diagnosed with more aggressive forms of breast cancer.

We are diagnosed with later stages of breast cancer,” Dedmon points out. “I think ..

. it’s a combination of systemic racism that is in the health care system ..

. social determinants of health (and) medical drivers that can be a barrier to our access to equitable, high-quality care,” she adds. Because of the lack of access to care and racial disparities in the health care system, medical history might be a sensitive subject for Black people, says , Ph.

D., medical historian and professor of African American studies at Yale University. “There’s a good amount of silence that is protective,” Roberts says.

“It’s about not wanting to relive an experience when bad treatment happens when there are feelings of shame, discomfort and pain.” Roberts describes Black people as “newcomers” to the medical industry “because we were excluded for so long.” These kinds of conversations are still being normalized, and many are clouded by misdiagnoses, and minimizing pain and illness in Black people.

For some families, agency feels accessible — family members advocate for it and have resources to lean on. While for others, these conversations still require a “profound vulnerability,” says Roberts. Still, they need to happen and thankfully, they’re becoming more common.

These conversations start at home, says Roberts, but if you have trouble accessing information about your family history, community centers and libraries are underused resources that offer details about Black medical history, she says. Even if you don’t have a family unit, you have the community. Health Reporter/Editor.