by JR Jayewardene (Excerpted from Men and Memories) The Ramgarh Session of the Indian National Congress, the last Session before Freedom was held in March 1940, in a small village, in Bihar Province, “sanctified by the touch of the feet of Gautama, the Buddha”, said the Reception Committee Chairman, Rajendra Prasad, later President of Free India. I attended the Session as a delegate of the Ceylon National Congress and recorded my impressions then. The little village of Ramgarh is today famous throughout the world.

For here gathered the men and women of the new India with her beauty and her chivalry, intent on freeing their motherland from foreign rule. It was a pretty countryside that we passed through on our way, for over a hundred miles to the west of Calcutta. Ramgarh itself is very similar to Diyatalawa, undulating valleys, large plains and mountain streams abounding.

It is also a countryside with a history unequaled in the world. The founders of Buddhism and Jainism both spent large portions of their lives in this province, now called Bihar. Bodh-Gaya is hardly a hundred miles away towards the north.

“Every particle of dust in this province”, said the retiring President, Rajendra Prasad to the delegates, “is sanctified by the touch of the feet of Gautama, the Buddha.” And as a tribute to India’s greatest son and to his disciple, Asoka, India’s greatest monarch, a facsimile, of one of Asoka’s pillars, over a hundred feet high, had been erected at the entrance to the Congress town. On this pillar the Congress flag was later hoisted, and as it fluttered in the breeze, the people of India paid their homage.

The new India they wished to create called them to action and this flag was their symbol. And how appropriate it was that a symbol of India’s ancient greatness should bear it aloft. Three huge pandals marked the entrances to the Khadi Exhibition, the open air arena and the Congress town or Hagar.

What was scrubby jungle had been converted into a small town. The main street was over a mile long and as broad as the Galle Road at Kollupitiya. Electric lights and a water service had been installed.

A railway station, radio and telephone exchange and a post office completed the township. Policemen there were, but none from the British Government. Men and women volunteers recruited as honorary workers from the district, controlled the traffic, helped those in,trouble and guarded the leaders’ huts.

And then came the inhabitants to this township. Over a lakh of people, a population larger than that of Kandy or Galle lived here for four or five days and then disappeared. They came from the North-West Frontier; they came from Madras, over two thousand miles away.

The women and children from every part of India, from every race in India, from every religion in India. Delegates and visitors from Burma, Ceylon, England and America. A Japanese monk was there beating his drum to drive away the evil spirits.

The streets were packed with a mass of humanity. There was bustle but no bluster. Everyone was friendly.

The mention of Ceylon brought forth a kindly smile and a word of greeting. The leaders of India were there, living simply like the rest, sitting on the floor while they ate, and mixing with the crowds. Mahatma Gandhi alone had a hut to himself.

Wherever he went he was mobbed. Crowds would suddenly break all barriers, rush up to his hut and shout: “Gandhi ji ki Jai”. His stay there was an endless series of interviews.

And thus to business. The work of the session begins with the opening of the Exhibition and the sitting of the Working Committee. The Working Committee was the “Cabinet”, and composed of about 12 members chosen by the President.

After that the All-India Congress Committee consisting of about 375 delegates from all the Congress Provincial Committees held its meetings. These meetings are held in a huge covered pandal capable of seating about 10,000 people. These were really the most interesting meetings.

For here took place the moving of motions and amendments for debate. For this purpose the Committee converted itself into the Subjects Committee. No motion or amendment rejected by the Subjects Committee had any chance of being accepted by the Session.

The Burma and Ceylon delegations were permitted to witness these deliberations. The Patna Resolution on Independence was the only official motion to be discussed. M.

N. Roy attempted to bring in a Communist amendment but found very little support. The motion was accepted without much trouble.

It was interesting to see these leaders of India. Perfect order was maintained. The leaders and the invited guests were on a huge platform covered with a large mattress and carpet.

The delegates sat on low benches in the body of the hall. The other visitors sat on the floor round the delegates. There were no chairs.

Girl volunteers in orange sarees kept order and served water. The Congress colours and flags were used to decorate the platform and the pandal. Abdul Gaffar Khan, over six feet in height, was there almost sleeping on the platform.

Mrs Sarojini Naidu found the low table on which a model charkha was kept more comfortable than the mattress. Pandit Nehru, quick of temper was calmed down by Jamnalal Bajaj, the Congress treasurer. He lost his temper more than once.

It was to a speaker from the Punjab who said, that “country is ready to fight, we are ready, the Congress is ready, but Nehru and Gandhi are not ready.” Nehru thereupon angrily retorted: “I am ready.” A young Communist speaker angered him terribly.

He rushed to the presidential table and exchanged a few words before calm was restored. And then came Gandhiji. Vallabhai Patel was speaking when he arrived, yet, it was only necessary to whisper, “Gandhiji is coming,” for the cheering to break out.

He slipped in quietly and sat on the floor. No remarks could anger him. When one of the speakers said, “It is this little man whom I can put into my pocket who is delaying us,” he laughed loudly and beckoned him to do so.

The resolution was passed unaltered and then Gandhiji spoke. He spoke for about an hour. There was no interruption.

There was no stir. Even those on the platform crowded round the speaker to hear his words. There is no doubt that Mahatma Gandhi, though not a member of the Congress, was its leader, nay, a dictator.

He said so himself. Congress, he said, cannot be a democratic assembly when it is waging war. It must become a fighting unit and it must have one general.

As long as they have him as general he expected unquestioned obedience. If they wished they could replace him and follow another. But could they? Thus concluded the meetings of the Subjects Committee.

And then to the sessions. Three days had been allotted for the open sessions. The Congress Sessions were held in a huge open air amphitheatre as large as the Victoria Park.

The members of the Congress Committee throughout India are entitled to vote, numbering over a thousand. At one end of the stadium was a platform and a rostrum for the President. The first day was allotted for the Presidential Address and the other two days for discussion on motions.

A crowd of over a lakh of people had assembled by 5 p.m. on the 19 March.

The President was expected at 5.30. More people were coming in.

And then came the rain! In half an hour the vast amphitheatre was one sheet of water and in some places the water was knee deep. The President’s speech was taken as read. Thus ended the Congress Session.

The next morning a make-shift session was held under the Asoka pillar, as the theatre was still wet and in a few hours the Patna resolution urging “Independence outside the orbit of the British Empire”, was passed. By the evening the crowds had started to leave. In a few days Ramgarh would assume its normal quiet.

The jackals would wander through the empty streets and huts. The aborigines will weave into their history the legends of Ramgarh, the story of a town which sprang up in a few days, of motor cars and trains and electric lights and of an “avatar”, an incarnation of God, whom they saw–Mahatma Gandhi. But what does Ramgarh mean to India and to the world? How were we in Ceylon to adjust ourselves to the results that flowed in from Ramgarh? Two facts were clear.

First, India was united in her demand to be free and she wanted her freedom outside the British Commonwealth of Nations. Secondly, Mahatma Gandhi was still the unquestioned leader of India. There was, no doubt, opposition to his leadership.

Subhash Chandra Bose held a counter show at Ramgarh with his anti-compromise and Forward Bloc ideals. These meetings were attended by the Kisan (peasant) organizations and had the support of over a lakh of people. The opposition were not, however, to Gandhi’s leadership: it was to his refusal to begin the fight.

His opponents wished to push him on to act at once. But Gandhi believed that the country was not ready and if he was the leader, he must give the signal to begin. In the Congress itself there was no opposition.

That India will begin her struggle again there was no question. That she would soon be free was also not to be doubted. In their minds and in their actions, the Indians were free.

They wore clothes made in India and used articles made in India. They did not recognize the British flag nor the British connection. To the men and women who thought as the political parties did, the British Crown and British ideals and customs meant nothing.

India was determined to travel on her own path to chart its own course. We, in Ceylon, had to learn many things. First, the idealism and complete absence of racial or personal feeling which characterized the political discussions at Ramgarh was a contrast to the petty methods prevalent among us.

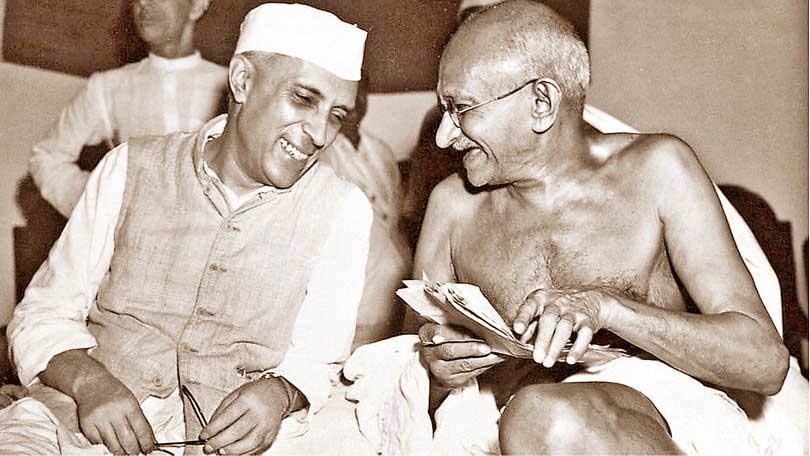

No man or woman we met, be he/she leader or the follower, talked except in terms of ideals of social and economic construction, of a new world order based not on exploitation but according to a planned economy. In the field of politics, the masses were trained to think not in terms of race or personalities, but in terms of social equality, equal opportunity for all and anti-imperialism. Could we in Ceylon close our eyes to these movements so close to our shores? Was it not the duty of our leaders, our men of letters and culture, or newspapers and all those who love this country, to quicken the awakening consciousness of our people and help them too to feel the impulse of that idealism which emanated from India? During the Ramgarh Session, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru who visited our quarters, after the torrential rains, asked us to visit him at Allahabad and stay with him for a few days.

Pandit Nehru was the only leader who visited all the guests and saw to their comfort after the rains. We gladly accepted his invitation and on our way to Delhi we called on him at Allahabad. John Ameratunge and I –J ayasekera had business in Bombay –stayed for a few days in Nehru’s house, “Anand Bhawan” on 26, 27 and 28 March.

We were treated with the greatest kindness and hospitality, as if we were old friends. Mrs Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, Nehru’s sister as the hostess, used to sit down for morning breakfast with us to a typical Western breakfast with bacon and eggs, toast and the host presided and sat with us. He would generally be out for lunch and return for dinner.

Indira Gandhi, his daughter, was not in India at that time, and we were the only guests. We had long discussions with Pandit Nehru though we were far removed from his activities which covered almost 20 years of direct and indirect non-violent campaigns, to free India from foreign rule. That campaign was now in its final stages and we talked to him quite freely about his role in these movements.

Like all other youths of our generation throughout the British Empire, we hero-worshipped Jawaharlal Nehru and his leader, Mahatma Gandhi. The friendship thus formed enabled me to correspond with him. Some of our letters have now been published.

They are letters that speak for themselves and unfortunately the correspondence terminated with Pandit Nehru’s incarceration. He was released just before the War ended and became Prime Minister of Free India and I became the Minster of Finance of Free Ceylon (Sri Lanka). We had many contacts but did not renew our correspondence.

“Quit India” – Indian Congress Meeting Bombay 7, 8 August 1942 The Indian National Congress had been preparing for a final move against the British rule since the Ramgarh Session. Its leaders had been arrested, tried, jailed and released. The British Government had sent Sir Stafford Cripps on a special mission to meet the Indian leaders; his mission had ended in failure.

The War in the West and in North Africa could not have followed a more disastrous course for the Allied Powers. In the East, Japan was in command of the Indian Ocean and had bombed Ceylon twice after the fall of Indonesia, Singapore and Burma. They were knocking at the doors of India on the Assam frontier.

It was at this moment that Mahatma Gandhi sought the sanction of the Congress to implement his “Quit India” program. I could not miss this opportunity. P.

D.S. Jayasekere, one of the Treasurers, C.

P.G. Abeywardene and I were deputed to represent Ceylon at the Indian National Congress Committee meeting to be held in Bombay to discuss the “Quit India” Resolution.

We accordingly left for Bombay through Madras by train on July 31, 1942. On arrival at Bombay, we contacted Jawaharlal Nehru on the telephone and he very kindly sent us tickets for admission to the special enclosure. We met him, his sister Mrs Krishna Huthee Singh and his son-in-law Feroze Gandhi at Mrs Singh’s flat where he was staying.

He was interested in hearing of the air-raids on Ceylon, the damage caused, and the consequences on the morale of the people. He was confident that India would be free after the War and did not favour a victory for the Axis powers. However, he said, he could not help the Allies as long as they (the Indians) were a subject people.

We met Mahatma Gandhi also at Birla House where he was staying. At our request he included Ceylon too in the Resolution demanding freedom for Asiatic nations. “Why do you think that Ceylon is not included in India’s demand for freedom?” he asked.

“My love for Ceylon is even greater than my love for Burma.- There was an amusing incident in the room. The late Mahadev Desai was seated on a cushion by the side of Gandhiji taking down his reply to a British paper.

At one stage Gandhi referred to the 380 millions of Indians. Desai playfully refused to take this down saying, “No, Bapuji, it’s not 380 millions but 400 millions”. Some of the others in the room also joined in the discussion regarding the exact number of India’s population.

Desai clinched the issue by saying that the latest census figure was 400 millions. Gandhi smilingly gave in, and allowed Desai to write “400 millions”. In spite of the bitterness that had arisen as a result of this conflict between Britain and India, it was true that in the mind of India’s great leader there was no hate whatever towards his adversaries.

The meeting of the Congress Committee was held under a large pandal seating 10,000 on the Gowalia Tank Maidan on 7 and 8 August 7 and 8. The meeting was more like a mass rally. The leaders were accommodated on a platform without chairs and we sat on the cushioned stage with them.

Mahatma Gandhi outlined his non-cooperation movement and called upon the British to “Quit India”, coining the now famous phrase “Karange Ya Marenge ...

...

Do or Die”. He was, by unanimous consent, accorded full powers to lead the movement. Soon after the meeting rioting broke out and as we left that very night for Madras we could not witness the varied forms into which it spread.

The train we travelled in was also stoned and throughout India similar occurrences were reported. Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and the other leaders were arrested. India was again set on the Gandhian path to freedom.

.