Holding faith dear to their hearts, settlers in the region constructed places of worship, from small cabins to majestic buildings. Before Confederation was in the works, and before Kingston was incorporated as a city, the cornerstone was laid for St. Mary’s Cathedral in 1843.

In the early 1890s, architects of the exquisite church at Johnson and Clergy Streets added the high tower and spires that stretch above the cityscape, making St. Mary’s a beacon, that called to the Catholic faithful. As the first Roman Catholic Bishop of Upper Canada in the early 1800s, Alexander Macdonell oversaw a vast diocese.

For about a decade, the bishop travelled to congregations from Lake Superior in the west to the Quebec border in the east. Macdonell “laid the foundation of his church in Upper Canada, going by canoe, on horseback and sometimes on foot,” writes Margaret Angus in The Old Stones of Kingston: The Buildings Before 1867 (University of Toronto Press, 1966). Granted permission to hold services at St.

George’s Anglican Church, Bishop Macdonell then held mass at St. Joseph’s Cathedral. At the same time, he made plans for a new church.

His successor, Bishop Remi Gaulin, began planning in 1842, starting with the appointment of Father Patrick Dollard to direct the project. The Irish missionary was familiar with Kingston, arriving from Montreal in 1836 to assist Macdonell at St. Joseph’s Cathedral.

As project manager, “Dollard raised the necessary funds by subscription in Kingston and Quebec, kept the accounts and supervised the construction,” said B.J. Price in Dictionary of Canadian Biography , Vol.

11, 1976. The land selected was among fields at the edge of the city and close to the Religious Hospitallers of St. Joseph—Hotel Dieu Hospital.

The original architects who designed the Gothic-style church are not clearly known. Many sites suggest it was James R. Bowes, however it appears he was not born until ten years after construction began.

(Bowes and his father, John Bowes, will reappear several decades later to perform architectural work for the church.) A majority of construction workers were already close by; members of the congregations volunteered to execute much of the labour. The cornerstone was set in place by Bishop Patrick Phelan in 1843, and the building began to emerge.

Pale grey limestone for the church’s façade was quarried on-site. Until the 1930s, when quarries began to close, local limestone was used for major Kingston construction projects such as Kingston Penitentiary, a number of beautiful churches, and government buildings. The church design featured arched windows and decorative carved stone ecclesiastical features.

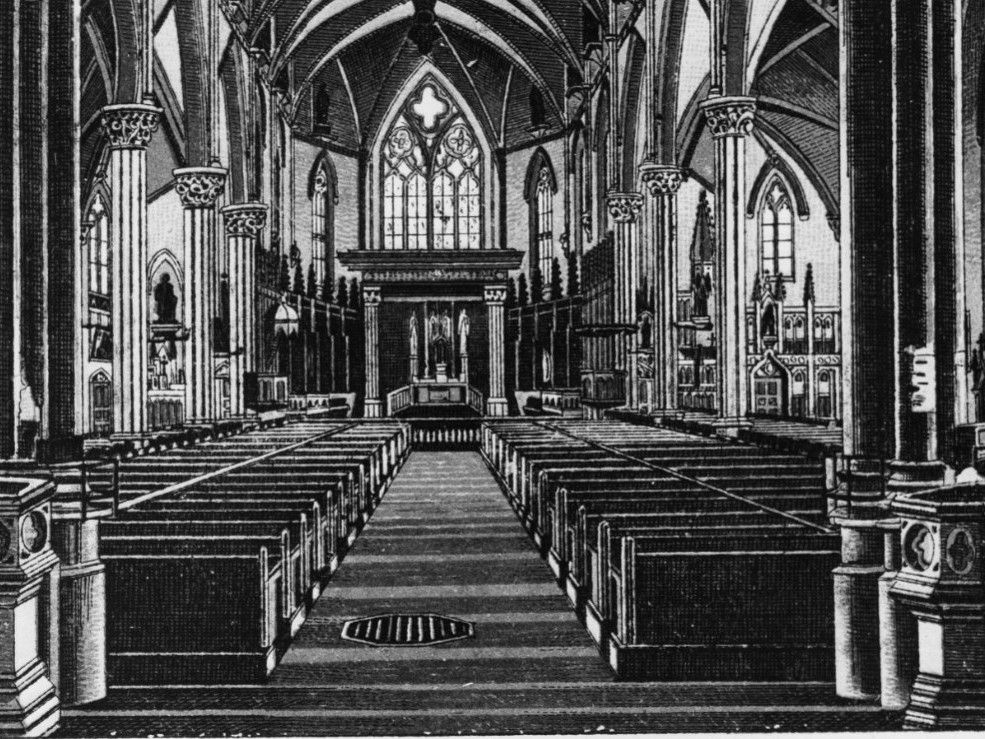

Set in arched entrances, elaborate wooden doors added weighty significance. The lofty columns in the cathedral were made from durable local hardwood trees encased with smoothed wood molding . “Their bases are plaster,” noted St.

Mary’s, “and each pillar is supported by limestone blocks which you might see in the crypt.” At first the building had “a single rather squat tower in the centre of the façade on Johnston Street,” said St. Mary’s.

The building “features rib-like buttresses along the east and west outer walls, which you will find echoed on the inner north wall behind the Bishops’ Throne.” Seated on wooden benches, parishioners looked toward the altar “beneath two tiers of plain glass windows.” Two sacristies were included–vestibules for storing vestments, sacred vessels, furniture, and more.

A tunnel was built between the church and the hospital so clergy members could respond to calls for urgent faith needs. (The tunnel is blocked off.) Ringing up at about $90,000, the spacious religious building measured “210 feet long (64 m) by 88 feet wide (26.

8 m),” according to Angus. The dramatic distance from the floor to the highest point of the vaulted ceiling reached 90 feet (27.4 m) Although construction was not completed for two more years, part of the St.

Mary’s building was in use by 1846. “Dollard was appointed first rector of the cathedral,” said Price. “As vicar general to bishops Gaulin, Phelan, and Edward John Horan, he was administrator of the diocese in 1857 and 1862.

” Regarded as agreeable fellow, the priest was frequently sought out by Kingstonians for religious and political discussions. Dollard pressed for educational rights, and “displayed a gifted mind in theology and scripture.” St.

Mary’s Cathedral was consecrated on October 4, 1848, by Bishop Patrick Phelan. The archbishop’s house, occasionally called the Archbishop’s Palace, was built shortly after. A substantial bell was installed in the tower and given the endearing nickname of Patrick.

The basement of the church included a crypt for clergy, plus nuns of Hotel Dieu Hospital and Sisters of Providence. Scottish-born Bishop Alexander Macdonell died while in Britain in 1840 and his remains were later returned to Kingston for interment in the crypt in 1861. Four more bishops were laid to rest in the church vault, plus one unusual person.

Passing away in 1881, Elizabeth Minnitt was the housekeeper to Archbishop James Vincent Cleary; the woman must have been held in high regard by her employers. Between 1884 and 1886, St. Mary’s Cathedral was enhanced with a new front façade, a soaring 61 m tower and spire, and six turrets, designed by architect James R.

Bowes (1852-1892). Additional plans were completed between 1889 and 1891 by architect Joseph Connolly (1840-1904). Six years earlier, Bowes’ father, architect John Bowes (1820-1894), had designed the “interior finishing of the cathedral, and new wood pews throughout the nave,” said Robert Hill of Biographical Dictionary of Canadian Architects.

In honour of Bishop Cleary’s elevation to Archbishop, St. James Chapel was constructed in 1889. The chapel features eight carved sculptures along the interior walls, representing St.

Mary’s first six bishops plus “Popes Leo XII who made Kingston a diocese and Leo XIII who made it an archdiocese,” according to St. Mary’s. Art with gold leaf and stained glass windows enriched the sacred space.

At about the same time, sixteen massive stained glass windows were added to the main church. Each window was about 9 m by just over 2 m, with six intricately designed panels and three symbols. The windows “tell the story of salvation from Adam and Eve until the deaths of Saints Peter and Paul,” according to St.

Mary’s. Crafted in England, the precious windows arrived in “the United States, where they were held pending the payment of duty.” Archbishop Cleary refused to pay the fee.

He contacted Sir John A. Macdonald, and the windows were delivered to Kingston. “Nobody knows whether the canny Scot actually paid any duty.

” A vibrant part of church services was music, supplied at St. Mary’s by an organist at the impressive pipe organ. Manufactured by Karn-Warren Organ Company of Woodstock, Ontario, the complicated instrument was installed in 1905.

Deteriorating over time, the organ was restored to musical glory in the 1970s. As years passed, more renovations have been undertaken. The church now has seating capacity for 1,500 congregants, and Patrick the bell was replaced and renamed after it was damaged in 1945.

Under the tender care of Father Shawn Hughes and his colleagues, St. Mary’s Cathedral remains a beacon welcoming all “wherever you are on your spiritual journey.” Susanna McLeod is a writer living in Kingston, Ontario.

.