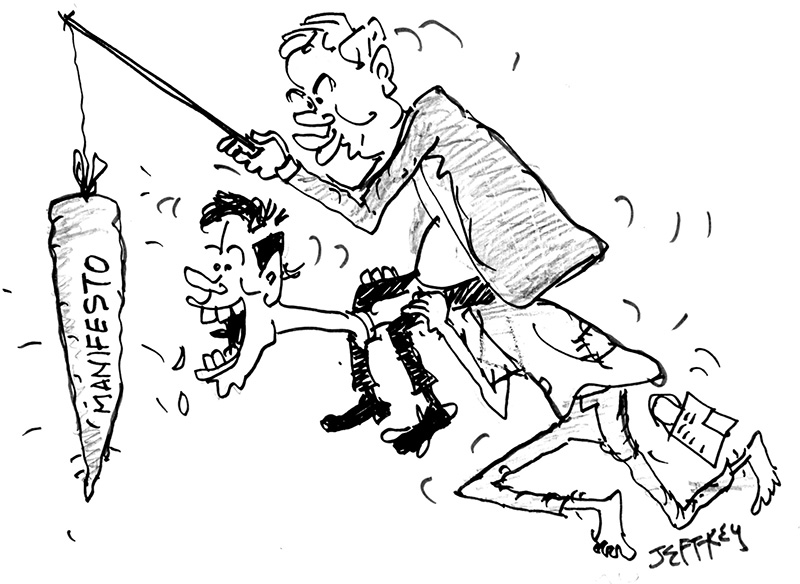

The Ranil’s manifesto claims that Sri Lanka became the “granary of the East” by adhering to Theravada economic policies, yet it does not explicitly define these policies. Instead, it contradicts this assertion by pointing out that Vietnam, a Mahayana Buddhist nation, followed Thailand’s lead. Despite Thailand’s traditional association with Theravada Buddhism, it adopted policies that resemble those of Mahayana-influenced countries like Japan.

These policies, particularly in the tourism sector, introduced revolutionary changes that seem contrary to Theravada principles, further complicating the argument. He also emphasized the relevance of Theravada Buddhism in addressing the challenges of a rapidly evolving world, driven by science and technology. Speaking virtually at the State Vesak Ceremony at Dharmaraja Piriven Viharaya, in Matale, on the 23 May 2024, he highlighted the need to preserve the core values of Theravada Buddhism and share its wisdom globally.

Buddhism, beyond its spiritual teachings, has deeply influenced socio-economic life across Asia. Theravada and Mahayana, the two main branches of Buddhism, offer contrasting views not only on religious practice but also on economic principles. Both schools emphasize ethical behaviour, compassion, and non-attachment to material possessions.

However, their divergent philosophical outlooks lead to varying interpretations of economic activity, wealth accumulation, and societal roles. Foundations of Economic Thought in Buddhism The core teachings of Buddhism focus on the Middle Path, a balance between indulgence and asceticism, with the ultimate goal of reducing suffering ( dukkha ). These teachings shape both Theravada and Mahayana views on wealth and economics.

Central to this framework is the Buddhist view of interdependence and the moral consequences of actions ( karma ). Economic activities, according to Buddhism, should align with ethical principles that promote collective well-being rather than personal greed. Ranil cites the Samaññaphala Sutta to assert that in Theravada tradition, loans should be used for investments, not consumption.

However, I could not find such a claim in the Samaññaphala Sutta ( Fruits of the Contemplative Life , translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu). Instead, according to the Singalovada Sutta, the Buddha taught that one should allocate only a quarter of their income for consumption, reinvest half of it to accumulate wealth, and reserve the remaining quarter for charity. Moreover, the Buddha emphasized, irrespective of Theravada or Mahayana, that failing to repay debts is a characteristic of an outcast ( Wasalaya ).

This suggests that loans should be used for generating income to ensure repayment, rather than for daily consumption. Theravada Economic Concepts Theravada Buddhism, often regarded as more conservative and focused on individual liberation, emphasises personal responsibility in the accumulation and use of wealth. It is dominant in countries like Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, and Cambodia, where economic behaviours often reflect the ethical values promoted by the teachings.

However, Ranil claims that Theravada economic policies are more export-oriented, but in reality, countries following Mahayana principles have been more successful in establishing export-driven economies. These Mahayana-influenced nations, such as Japan and China, have achieved greater success in building robust export-oriented systems compared to traditionally Theravada countries. In Theravada Buddhism, the goal of life is personal enlightenment ( Nirvana ), and material wealth is seen as a potential obstacle if it leads to attachment.

While wealth is not condemned, its mindful use is emphasized. Individuals are encouraged to follow “right livelihood,” engaging in ethical professions that do not harm others. Wealth is valued when used for virtuous purposes, such as supporting family, charity, and religious institutions.

Generosity ( Dana ) is a key practice, believed to purify the mind and aid spiritual growth. Theravada also promotes social stability through wealth distribution, with the laity supporting the monastic community in exchange for spiritual guidance, fostering economic interdependence without excess materialism. Mahayana Economic Concepts Mahayana Buddhism, prominent in East Asia (China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam), offers a broader, more inclusive approach to spiritual practice.

It emphasizes the Bodhisattva ideal, where individuals work not only for their own enlightenment but also for the liberation of all beings. This collective focus shapes economic views, promoting wealth as a tool for social responsibility and reducing suffering on a societal level. Wealth is seen positively if used altruistically, encouraging large-scale philanthropy, social welfare, and efforts to address inequality.

Unlike Theravada’s focus on personal morality, Mahayana stresses compassionate action ( karuna ) and societal transformation to tackle the root causes of poverty and inequality. Wealth, Ethics, and Capitalism In both Theravada and Mahayana, wealth is viewed through an ethical lens, but with distinct approaches. Mahayana, with its broader focus on social responsibility, aligns more easily with modern economic systems like capitalism, viewing wealth creation as an opportunity for the greater good if guided by ethical principles.

Theravada, on the other hand, takes a more cautious stance, promoting a simpler lifestyle and warning against excessive material accumulation. In Theravada societies, the monastic community ( Sangha ) provides a moral check on economic inequality. Mahayana’s emphasis on compassion has also led to socially conscious enterprises in East Asia, prioritizing sustainability, fair labour, and ethical products, reflecting the Bodhisattva ideal of using wealth for humanitarian purposes.

Ranil claims that Theravada economic policies are more export-oriented, but in reality, countries following Mahayana principles have been more successful in establishing export-driven economies. These Mahayana-influenced nations, such as Japan and China, have achieved greater success in building robust export-oriented systems compared to traditionally Theravada countries. Sri Lanka, as a predominantly Theravada Buddhist country, has a long history of intertwining its religious principles with governance and economic policies.

However, a critical examination reveals that the country’s modern economic policies, shaped by globalization and capitalism, increasingly diverge from traditional Theravada Buddhist concepts. While Sri Lankan society continues to emphasize Buddhist values in various aspects of life, its capitalistic economic structure suggests a closer alignment with the broader, more flexible economic interpretations found in Mahayana Buddhism. Sri Lanka’s Capitalistic Economic Policies Post-independence Sri Lanka has seen significant shifts in its economic policy, particularly following the liberalization of the economy in 1977.

These changes introduced free-market principles, deregulation, and foreign direct investment, which moved the country toward a capitalist economic model. The focus shifted from self-sufficiency and state-controlled economic activities to embracing global trade, privatization, and open markets. The rise of private enterprise, multinational corporations, and consumer culture indicates a move away from the traditional Theravada ethos of simplicity and non-attachment.

In this context, the rapid urbanization, expansion of tourism, and increasing wealth inequality seem more aligned with capitalist values, where material success and profit maximization are prioritized over ethical considerations of wealth distribution Closer Alignment to Mahayana Economic Principles Sri Lanka’s capitalist policies reflect this Mahayana-like flexibility. Wealth accumulation, entrepreneurship, and international trade are embraced, but with a growing focus on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and philanthropy. Large corporations and wealthy individuals are often seen contributing to charitable causes, building schools, hospitals, and donating to religious institutions.

These actions mirror the Mahayana ideal of using wealth for the greater good, though not necessarily limiting personal accumulation. He claims that many countries have succeeded by promoting private enterprises and that his Theravada economic system will be a much broader version of this. However, he does not clearly explain how this broader approach—typically associated with Mahayana tradition—aligns with Theravada principles.

In fact, most of the economic concepts he references stem from Mahayana traditions. By invoking the term “Theravada,” he seems to be appealing to the Sri Lankan Buddhist community, assuming that people will be swayed by this rhetoric, much like they were with the Kelani River cobra myth and Safi’s allegations, which were sensationalized by certain media outlets. Consumerism and Buddhist Values Sri Lanka’s burgeoning consumer culture further highlights the tension between traditional Theravada values and the realities of a capitalist economy.

The rise of consumerism, especially in urban centres, encourages material accumulation and status competition, which is antithetical to the Theravada emphasis on contentment and non-attachment. Advertising and media increasingly promote luxury goods and services, feeding a cycle of desire and consumption that stands in contrast to the Middle Path. This mirrors trends seen in Mahayana Buddhist countries like Japan and China, where consumerism exists alongside Buddhist practice.

In these countries, Buddhism has adapted to modern economic realities by focusing on charitable giving and social responsibility rather than strict asceticism. Social Welfare and Wealth Redistribution Sri Lanka’s current economic policies diverge from traditional Theravada Buddhism, which emphasizes wealth distribution through support for the Sangha and charitable acts. Instead, Sri Lanka has experienced growing inequality, with urban elites benefiting more from economic growth while rural and marginalized communities remain impoverished.

In contrast, Mahayana Buddhism’s Bodhisattva ideal aligns with the state’s sporadic welfare programmes and redistributive policies, such as free education and healthcare. However, these programmes are often hindered by inefficiencies, corruption, and a capitalist system that prioritizes profit over equitable growth. Conclusion Ranil’s emphasis on aligning his policies with Theravada tradition appears to be more of a marketing gimmick or salesman’s puff—an overstated claim intended to persuade the predominantly Theravada Buddhist community, which believes that Theravada concepts are original Buddhism.

This community has lost faith in his commitment to protecting Buddhism as required by the Constitution. By invoking Theravada values, he likely aims to regain their trust, despite the exaggeration or lack of doctrinal grounding in his statements..