Long-term, low-dose antiviral treatment reduces the risk for potentially vision-damaging bouts of inflammation and infection, as well as pain, which occur when shingles affects the eye, according to new research presented October 19 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) in Chicago. Shingles occurs when the varicella-zoster virus, which causes chickenpox in children, lies dormant for decades in nerve cells and then starts multiplying again for reasons unknown. It commonly affects people 50 and older, and adults with impaired immune systems due to disease or treatment.

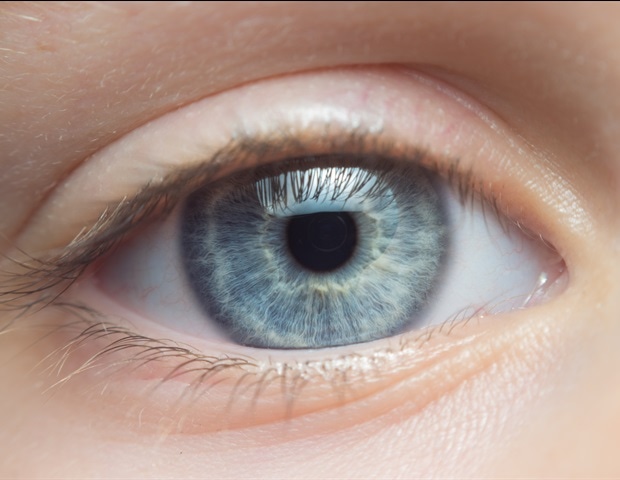

The virus spreads down a nerve pathway to cause a painful blistering rash in the skin area that the nerve wires. In about 8 percent of the more than 1 million new shingles cases in the United States each year, the virus awakens in the nerve that supplies the forehead and eye, a condition called herpes zoster ophthalmicus, or HZO. Shingles causes keratitis when it affects the cornea, and iritis when inside the eye, with both causing pain, redness, decreased vision, and sometimes glaucoma.

Repeated flare-ups are associated with chronic eye disease, scarring, and vision loss. The new research, part of the eight-year Zoster Eye Disease Study (ZEDS) and presented at the AAO meeting's Cornea Subspecialty Day, shows that study participants treated for a year with a low dose of the inexpensive and safe antiviral drug valacyclovir (Valtrex) saw a 26 percent reduction in their risk of having .