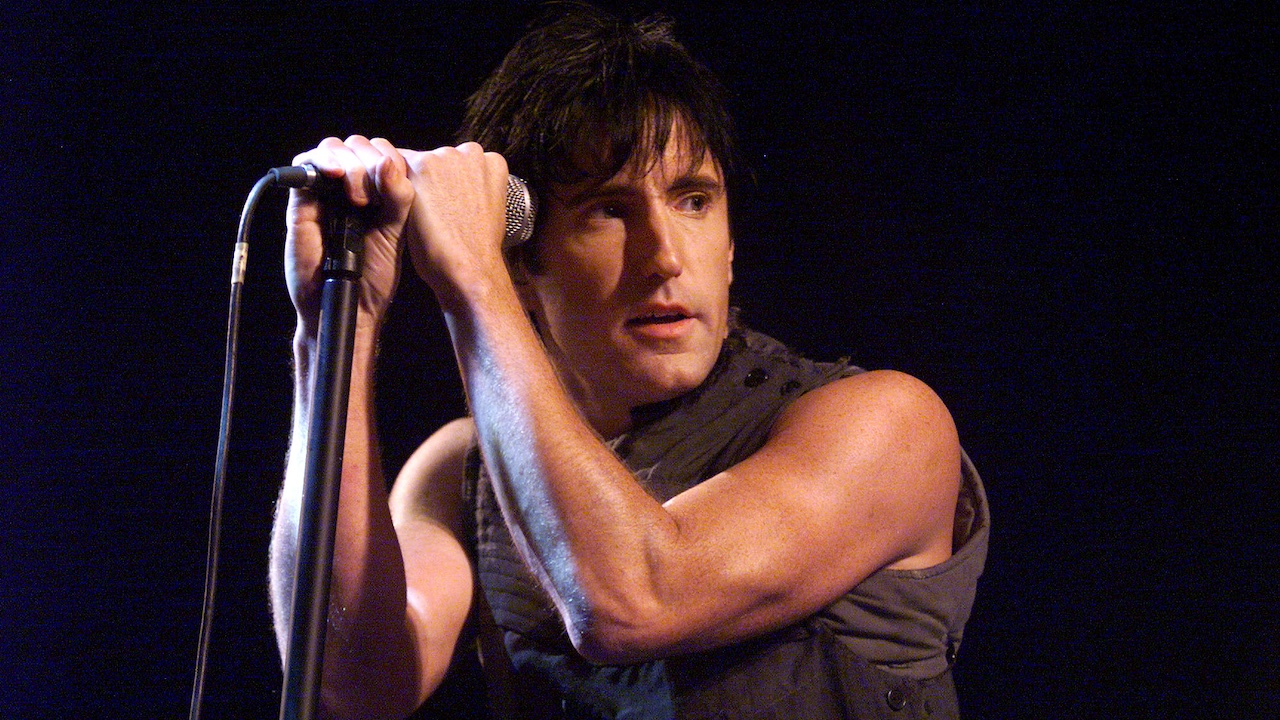

Few artists in the '90s inspired such fervent devotion as . With 1989’s Trent Reznor brought industrial metal to the masses, and with 1994's altogether more unsettling concept album , he became one of the poster boys for Generation-X's frustration, pain and mental turmoil. Nine Inch Nails' music made Reznor a superstar, yet, far from giving him the inner peace he craved, it actually seemed to make him even more unhappy.

Battling various demons, and self-medicating with heroin, cocaine and alcohol, Reznor all but vanished in the second half of the 1990s. But when he returned, he did so with an album that was even more complex, dense, dark and personal than anything he had or would ever put his name to again, Nine Inch Nails’ sprawling masterpiece Somewhat ironically, for Nine Inch Nails' creative mastermind, the success of would lead to life imitating art. Amid the relentless schedule of the infamously tumultuous Self Destruct Tour, with his fanbase expanding and his profile rising, Reznor began to unravel, and his addictions escalated.

Much like his character on the album, he began to loathe himself, and appeared hellbent on systematically tearing his world apart. “I really just hated myself,” he admitted to magazine in 2005. “I got to a point where whatever shred of liking I had for myself was lost.

I was on a fast path to death.” Upon the conclusion of the tour, Reznor had always intended taking an extended break. But when an offer came in for NIN to support his.