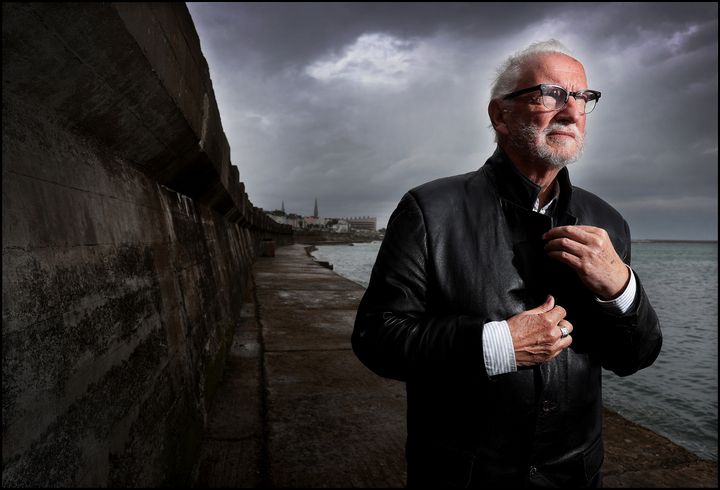

Tony Boland, the former music director on the RTÉ show, on working with Gay Byrne and Bob Geldof, helping create the Self Aid telethon and setting up an annual festival celebrating one of music’s most maligned instruments Tony Boland, former Late Late Show musical director. Photo: Steve Humphreys Gay Byrne and Tony Boland on the Late Late Show set For much of 1979, on a Friday afternoon, Tony Boland received a call from the same young man. Every time, the request was the same: “If you have a cancellation, can we go on?” Tony Boland was the music director of The Late Late Show .

It was he, rather than Gay Byrne, who decided what acts should get to appear. The eager caller was Larry Mullen Jr and, eventually, his band was invited to play the country’s preeminent TV show. U2 made their Late Late Show debut on Saturday, January 5, 1980, delivering a spirited version of Stories for Boys .

It was a leg-up to the superstardom that would soon come their way. Today, Boland, a youthful looking 82-year-old, smiles when recalling the drummer’s persistence. “He was very polite and would phone every single week for about six months.

” Boland had been well aware of the fledgling U2, but there were many local bands at the time who warranted the exposure that the Late Late guaranteed. Mullen’s calls paid off, though. “I began to feel a sense of responsibility,” Boland says, with a chuckle.

“They were really enthusiastic.” Eventually, Boland offered them a slot — for December 1979 — only to have to pull it. “That would happen quite a bit.

We’d tell the bands that there was a possibility that there could be a change [to the show’s schedule] but I don’t think U2 ever quite forgave me!” In fact, they mentioned being ‘bumped’ from the show when gifting a motorcycle to Gay Byrne on his last ever show as host in 1999. Tony Boland worked on The Late Late Show from 1970 to 1988 — its imperial phase, essentially — and his impact on Irish music can’t be overstated. He was one of the key drivers of Self Aid — which offered an unparalleled line-up of homegrown talent on a one-day, televised bill — and even before joining RTÉ, he had been instrumental in promoting Dublin’s beat music scene in the mid-1960s.

A proud ideas man, he still has an impact — the now annual festival, Ukulele Hooley, which takes place in Dún Laoghaire this weekend is his brain child. Boland is a great raconteur and there is a lot of ground to cover but, first, what on earth made him champion one of popular music’s most maligned and misunderstood instruments? “I’d never been interested in the ukulele,” he says, when we meet at a restaurant close to his south Dublin home, “but one day when I was driving and listening to Dave Fanning, he played a record, Somewhere Over the Rainbow , by a guy called IZ Kamakawiwo’ole. He was this gigantic, Hawaiian man [who died in 1997].

Something piqued my interest listening to that track and when I got home I started researching ukuleles.” He was 65 at the time and soon found himself going down a ukulele-shaped rabbit hole. “There was only one shop in Dublin that sold them and they were basically plastic toy versions.

I bought one online from Hawaii. I’d never played an instrument even though I’d been involved with music all my life and I decided that four strings [rather than the guitar’s six] couldn’t be too hard.” He learnt how to play the instrument and still picks it up most days, but cheerfully suggests he is the world’s least talented ukulele player.

Like most summer festivals, the Ukulele Hooley started out small. It was first held in Temple Bar in 2009 and, in 2011, it found a home in Dún Laoghaire’s People’s Park. With the exception of the pandemic years, it’s been held every summer since.

The performances are free and Boland stresses the family-friendly nature of the events. Ultimately, he insists that anyone who attends will be left in no doubt about the virtuosic nature of the instrument. He is evangelical when talking about the ukulele.

“It first came to international prominence during the world’s fair of 1915.” Subsequent research shows that that San Francisco-hosted fair helped launch a veritable craze, although it’s also the case that many of the globe’s most prominent acts happily eschewed the ukulele. Years of high-pressure media work had taken their toll: ‘I remember flying into Los Angeles to have all these meetings and on the face of it, it all seemed so good.

But I realised I didn’t have the hunger I once had. I was burnt out’ Boland stepped away from the management aspects of the festival some years ago, but delights in how it’s become a key part of the coastal town’s summer offering. For the past 26 years, he has practised as a psychotherapist — having worked alongside the late Ivor Browne — and he seems entirely uninterested in the notion of retirement.

Years of high-pressure media work had taken their toll and he was happy to take an entirely new direction in his 50s. “I remember flying into Los Angeles to have all these meetings and on the face of it, it all seemed so good. But I realised I didn’t have the hunger I once had.

I was burnt out.” He went on to study psychotherapy and soon experienced transformation. “I love working with people,” he says.

“The whole thing about psychotherapy is that it’s all about loss of some sort. It could be loss of self, grief, loss of hope and what I’m trying to do is find a way through and help people.” Boland’s love of popular music was burnished when he moved to London in 1960 when he was 18.

While studying journalism during the day, he did night shifts at the Irish Independent ’s London office. It was an exciting time to be young in that metropolis. The UK was emerging from a post-war slump and rock and pop was leading the charge.

He became friends with a young upstart, Andrew Loog Oldham, who went on to manage the Rolling Stones in their formative years. Having married young and with a baby on the way, Boland and his English wife returned to Dublin in 1963, a matter of weeks after the Beatles had played their only Irish show at the long defunct Adelphi. He kept at the journalism — and had a pop column in the Evening Herald — but diversified, too.

For a while he was handling public relations for the Clancy Brothers — he got the gig thanks to veteran journalist Joe Kennedy, who had been friends with Liam Clancy. The showband scene was mushrooming in the 1960s, but there was plenty of other, much more interesting, music too, especially in the heart of Dublin. There were several beat clubs including Sound City, which Boland opened on Burgh Quay in 1964.

Gay Byrne and Tony Boland on the Late Late Show set For much of the ’60s, he was a young man going places. And, so too, of course, was Gay Byrne, with whom he would have a close working relationship as soon as he was hired by RTÉ. “In all honesty,” he says, “I learned more from that man than I did from anybody else in my life.

He was the most incredible professional about everything he did. He knew exactly what he wanted, but he was very open. You could come in with any idea in those Monday morning meetings.

He’d push you really hard to make sure you really believed in the idea and then he’d let you off to go and do it. “He knew his audience and was always willing to change with them. He watched for change all the time.

” Boland also believes that Byrne, in his pomp, did not shy away from featuring the sort of contentious guests who tend to be avoided by mainstream broadcasters nowadays, who are petrified of causing offence. While U2 were booked to appear on the show on many occasions — usually as talking guests rather than actual music acts — Boland has fond memories of two music performances. One was from the singular American songwriter and actor Tom Waits, the other courtesy of renowned violinists Stéphane Grappelli and Yehudi Menuhin.

It was Boland who had the Boomtown Rats appear on the Late Late for the first time and he became close to Bob Geldof. Years later, as Geldof was preparing for the huge Live Aid concert, Boland gave him the idea of doing a fundraising telethon on the BBC. As he remembers it, Geldof had originally planned to sell the rights to the European Broadcasting Union, of which RTÉ is a member, but Boland had told him that much more money would be gathered by forgetting about TV rights and instead appealing directly to the public.

RTÉ’s telethon — hosted by Byrne, Mike Murphy and other luminaries during breaks in the Live Aid schedule — helped raise more cash per capita than any other country. Soon, Boland — along with another senior RTÉ producer Niall Mathews — had the idea of putting on a mega concert and telethon to help create jobs in an Ireland scarred by unemployment. Self Aid took place in Dublin’s RDS in May 1986 and featured everyone who was anybody in Irish rock and was broadcast live over 14 hours.

“I’m very proud of it,” Boland says. “What it did was to give a lift to a lot of small businesses and we had firms contacting us that day and saying, ‘OK, we’ll make a commitment to take somebody on for a year.’” Geldof was one of the first people he called when he first had the idea.

Later, the two would set up a production company together, Planet Pictures, specialising in arts programmes and the behemoth that was The Big Breakfast . Soon, Boland was dealing more with Channel 4 executives than their RTÉ equivalents, but that career change to psychotherapy was soon around the corner. The ukulele, however, was still a long way into the future.

The Ukulele Hooley runs until Sunday. Visit ukulelehooley.com .

.