Despite facing borderline insurmountable competition when the firm first got up and running, Neural DSP has not only managed to enter the digital guitar gear market, but it’s been able to rise straight to the very top. And it has done so in just six years. First, founders Doug Castro (CEO) and Francisco Cresp (CPO) set about innovating a suite of state-of-the-art plugins – and, later, signature packages – which have since been championed by numerous high-profile artists, Tim Henson, Mateus Asato and Cory Wong among them.

Then, they sought to pioneer an amp modeler multi-effects pedal in record time, which would eventually flip the market on its head upon release. Indeed, after debuting at NAMM 2020, the Quad Cortex quickly became the gold standard of its kind. That’s no mean feat, especially when one considers the competition Castro and Cresp were up against.

Line 6, Fractal, Kemper and Boss all had years-long headstarts over Neural DSP, but by combining world class tones with unprecedented consumer tech-level functionality, the Quad Cortex cemented its status as the do-it-all digital floorboard unit for countless players. Such competition, though, necessitated an outside-of-the-box approach – one that would not only help Neural DSP assemble an archive of digital amps and catch up with the competition, but also allow it to exceed its rivals in terms of tonal performance. To do so, Neural DSP quietly began working on a robot, which, after years of living outside the limelight, was recently unveiled .

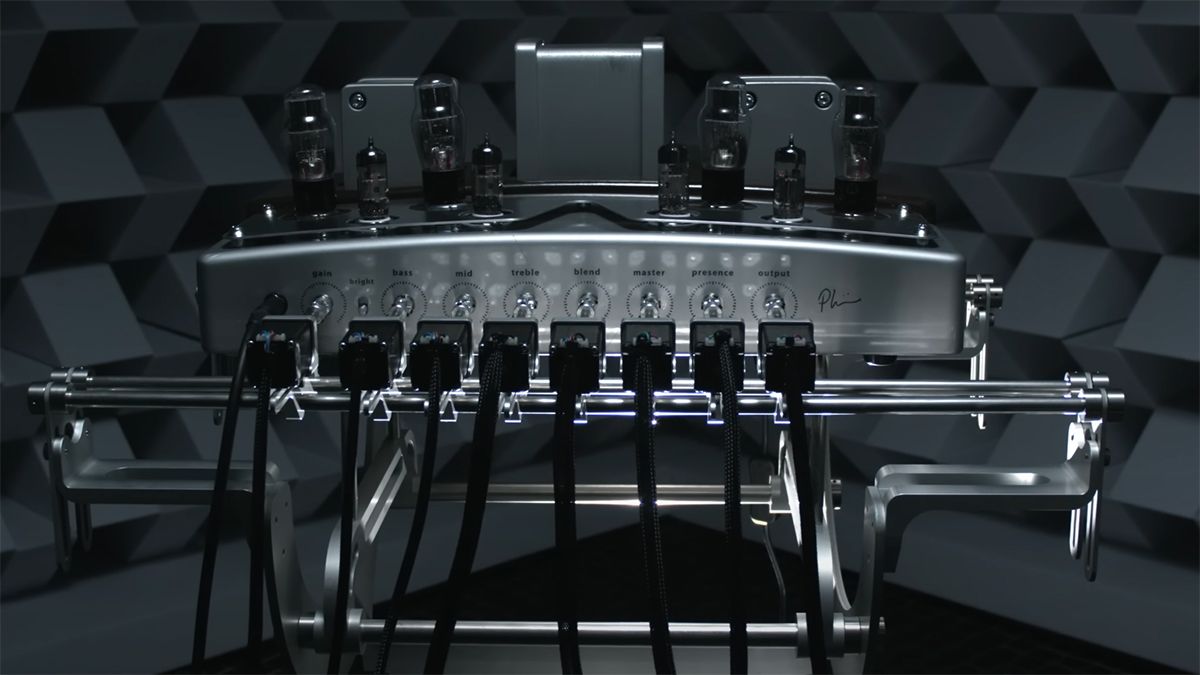

‘Telemetric Inductive Nodal Actuator’ – or TINA, for short – has been a key driving force behind Neural DSP’s success, though it has never been singled out for its impact. It is supposedly able to authentically and faithfully model the sonic nuances of a guitar amp at “an unprecedented level”, offering “unparalleled precision and speed”. The robot – which attaches to an amp via actuator arms – is “faster, smarter and more accurate than any human”.

And its success is clear to see: everything that Neural DSP has worked on has at some point gone through TINA, from its flagship Fortin Nameless plugin to its Archetype packs. It’s no exaggeration to say that, without TINA, Neural DSP may be a very different company today. Now, with Quad Cortex and plugin compatibility finally becoming a thing – giving players the chance to use TINA-created plugins with the floorboard – the fruits of the robot’s labor have been given the spotlight.

In a wide-ranging interview with Guitar World, Castro and Cresp discussed the firm’s journey so far, how TINA has helped them change the digital gear game, and the current state of the modeler market. When you first started Neural DSP, what was your mission? Doug Castro: “Francisco and I worked together at Darkglass Electronics, and we would talk a lot because we're both really passionate about gear. One of the conversations we had was about what type of gear guitarists will use in 20 or 30 years from now.

From that, the dream of the Quad Cortex came about. “A lot of the features that are in the Quad Cortex stem from asking those simple questions, and then we realized there's no reason to wait 20 or 30 years to do it. We thought, ‘Can we do it 10 times faster?’ After talking about these ideas, it became clear we should do them under a new brand.

Darkglass is known as a really good bass company, but clearly the guitar is the bigger market. It was clear that although riskier and scarier because we would start from nothing, a new run was the way to go.” In the face of competition from Boss, Line 6, Fractal and Kemper, how did you manage to break into the market and achieve the success you have had in such a short space of time? Castro: “We have a lot of respect for the companies you mentioned.

They're great companies that have done great things. We studied their products very carefully – Francisco, especially, did a very deep dive on the features and limitations of everything – and came up with a list of specifications that gave us what we thought each company did best, while trying to cancel out what we thought they were doing the worst. “We tried to make a product that had all of the strengths of our competing products while trying to have none of the limitations.

In the conceptual phase, at least, that was the idea.” Francisco Cresp: “There's several things that we tried to accomplish, but a key point was ease of use. There's no unit in the market that would be easier to use for people that are a bit more afraid of the digital market.

“And with the quality of sound, we were able to establish the brand by releasing plugins earlier and get our place in the market. Also, people really love the user interface on the Archetype plugin series. That gave us an edge on ease of use and quality of sound, which I think is basically the stamp of the brand.

“With the Quad Cortex, we had some other advantages, like the touchscreen and all the hardware design. We got rid of as many breakable parts as possible, and came up with a design for a rotary switch that works as a footswitch as well. We took the Capturing technology to the next level, improved connectivity, offered some phantom power, and used inputs for people that want to use it with acoustic instruments and not just electric guitar .

We came from many different fronts, but the quality of sound and usability are the two key aspects.” Castro: “When it comes to something like the Axe-Fx or Kemper, there were two key aspects that we thought made these products really appealing. One is, ‘How good do they sound?’ In the case of modeling an amplifier, how accurate is the model? The other is, ‘How easy is it to use?’ “We realized very quickly that there wasn't much room for improvement on sound quality.

We thought that maybe you can do slightly better – you know, do one or two percent better, or just match that – but when it came to ease of use, there was definitely room for improvement. “Back then, there was this interesting dichotomy: you had to choose either ease of use, or really good sound and power. Units that were really powerful and sounded really good were hard to use, and units that were really easy to use usually didn't sound that good and weren't as powerful.

“We thought, ‘Why?’ Why can't anyone make something that sounds just like the real thing and is as easy to use as your tablet or your iPhone? That's a lot of the work that Francisco did in designing the user interface with our designers: making sure that it was super intuitive, while ensuring the sound was also there. From the get go, we realized that was what we had to do in order to enter the market to compete and do well.” In the simplest terms, what is TINA, and how do you use it? Castro : “With the Quad Cortex, we had to compete with products that have been around for five to 10 years, so we had to find a way to do five to 10 years of algorithm research in two years.

“The conventional methods require white box modeling, where you analyze the circuit and then create a model based on simulating the circuit. With those approaches, you're always dependent on how good an engineer you have. And initially, you need PhD-level knowledge to do these things.

These people are really hard to find, very expensive, and they have really rare skills that are really hard to acquire. And there's only so much they can do in a day. It was impossible for us to have hundreds of amplifier models in two years.

“The only thing that wasn't impossible was to automate the whole thing. We started working on this six or seven years ago. Doing it the conventional way was simply unviable.

Automating everything was almost impossible, and we had a less than 10% chance of succeeding – but a 10% chance is better than 0% chance. That’s when we started recruiting more machine learning researchers and working towards automating the full process. “What TINA does is it turns the [amp] knobs in a very specific sequence so that we can not only learn how the amplifier behaves in any given setting, but also how the knobs interact with each other, and how that affects the other signals.

“With that, we were able to cut down the time. Fender mentioned that for the Tone Master Pro, it takes one of the researchers about three months to model a channel. That's about the same time that our more conventional DSP engineers needed to make an amplifier.

With TINA, we've got that down to hours or, worst case scenario, days. It’s exponentially faster. “Another benefit of TINA is, if you don't know – or if you cannot quantify – what an element of an amplifier does for the signal, you will not take it into account in your model.

The good thing about basing a model purely on measurements is that, if it has an effect on the signal, we will be able to measure it. “It will be taken into account in the model, which gives us the same quality but 100 times faster. it gives us better precision, better accuracy and, therefore, better quality.

It’s an exponentially better method for modeling amplifiers.” [Fender’s Director of Product Management Jason Stilwell revealed it takes Fender three months to model an amp in the December issue of Guitarist magazine : “Each amp model takes around three months to complete from the day the engineer starts coding, then there are many listening tests until we feel the model is dialled in” – Ed.] Has it been used to model all the amps you've put out in your plugins? Castro: “Yeah, and pedals.

Even compressors as well. We're now doing more complex compressors.” How come you’ve decided to unveil TINA now? Castro: “That was more of a strategic decision.

We did this big marketing campaign recently, but our engineers published a paper on it a few years ago. We filed for patents for it also years ago. If you look at the European patent database, you'll definitely find drawings.

“We started to make a big deal of it now because we thought that, with Quad Cortex/plugin compatibility, it just made sense to put those two things together. In hindsight, it might have been good to do them separately, because now people are confused.” To clarify then, is it a physical robot? How many do you have? Castro: “Yes.

We have several. That's another beautiful thing: if you wanted to double your rate [of modeling amps ] you’d need to hire more people who are really hard to find to begin with. If you just build a new robot that costs about $100 to make and takes a couple of days to build, you’ve doubled your research capacity.

And you can scale it indefinitely. We could have, if we ever needed to – I hope we don't – 100 robots working in tandem.” It’s fast, it sounds better, it’s cheaper.

.. What impact could this sort of tech have on the wider industry? Cresp: “Even though this sounds really good, it took us a long time to get where we are.

There were a lot of failures and difficult situations. There were also lots of difficult amplifiers – like, there’s a Mesa/Boogie with three-way switches and faders. Sometimes amps start misbehaving when you push the master volume too hard or the signal is too loud.

“We learn through doing and we have perfected the system, and now we can scale it up a lot faster. But it was a really long road, and we are at the forefront of this technology a lot more than people think. “Of course, we can't show our secrets to the world.

But I think, because we published the papers and let the world know how we're modeling our devices, this will definitely encourage the rest of the industry to do something similar. And we are applying it to different devices that are not just guitar amplifiers or pedals.” Is the end goal to have a robot that can automate any effect, any amp and any studio compressor? Is that where you see this project going? Castro: “Yes, that's the goal.

And even time effects as well. It's something that we don't know is possible yet, which means that it’s something our development and research team need to keep working on. But we're definitely pushing our engineers pretty hard, and they're magnificent at what they do.

So if it's not impossible, then I'm sure we'll find a way to do it sooner or later.” If you’ve got this archive of digital amps, then do you think their physical source material will ever become redundant? Cresp: “I think there's always space for analog gear. There's a lot of people that just like the experience of a tube amp .

We love them too – that's why we do what we do in the first place. They're just sometimes inconvenient. Flying gear all over the world is tricky.

“But I think there's always gonna be a space for them. And at the same time, the models we create in the Quad Cortex or in the plugins are the specimens that we have ourselves. We try to study them as much as possible so we can get them to the spec they were supposed to be as created by the manufacturer.

“But a lot of these vintage amps have been manipulated in one way or another. People can have the same amplifier that sounds completely different, and that's where Capture shines, where people can capture their own gear. We make what we think is the most versatile model of an amp specimen we have available, but I think there's always space for collectors or rare items.

” What would you say is the most difficult amp you’ve ever modeled? Cresp: “Mostly amplifiers that have a lot of combinations. For example, the [Mesa/Boogie] IIC+ was a difficult one because, first of all, it was a very rare item to get your hands on. They have a lot of channels, and pull and push knobs, and different types of combinations with the graphic EQ.

There's a lot of complications and we had to create a very complex training system for that amp. “But we work really hard to get those models as close as possible to reality, because they are rare items that less than 0.1% of musicians will ever see in their lives.

Our story was based on trying to rescue vintage gear that is almost impossible to get. The opportunity for people to try them is almost null, so making this available for everyone is the goal.” I guess that’s another big part of the project: giving people the chance to play amps they would otherwise have no chance of playing.

Castro: “Yeah. The Fortin Nameless, which was our first guitar product, is a good example of that. It was an amplifier that Mike Fortin made very few of.

It was a very limited run – 100 or something – so there's only so many of those amps available that you can buy, and the resale price is really high. But with us you can get a perfect model of it.” Is there a piece of gear that’s really hard to get a hold of that you’d like to take a look at and model? Castro: “I would love – I think a lot of people would love – for us to do a Dumble at some point.

I mean, if you talk about rare unicorns, that's the amplifier. And to have something that John Mayer himself couldn't distinguish from the real thing, then I think it's something that a lot of our users would love. That’s something we would love to do eventually.

” Do you think that would be an easy one to model? Castro: “It's hard to say. Sometimes you put these models in the robot, and 24 hours later you have a model that everybody's like, ‘Yeah, that's it.’ Sometimes you do have some iteration where the designers need to tweak things and try again.

“It really depends a lot on the amplifier. And our own methods have evolved a lot. We've been using this tool in some shape or form for five years now.

But what we do now is very different from what we did four years ago. It's continuously improving and evolving.” What are your perspectives on the modeling market today? Cresp: “Something to mention is that we always thought ‘neural networks’ [the technology behind the Captures that gave the company its name] were the way to go, because we had to create a library from scratch, and had to create a hardware product in a record time.

“With the plugins, we started creating our library slowly, but in the background we worked a lot on the hardware unit. We knew that with traditional DSP techniques it would take us a lot longer, so we started developing this technology, which now you finally see with TINA being revealed. I think the industry lately has moved a lot towards that direction.

Part of it is our premise of trying to disrupt that traditional method and trying to invent something new and take things in a different direction. “Also, I do see the industry moving forward with AI in general in the audio market in several aspects, and not just audio amplifier modeling or pedals modeling. There's a lot of tools now that are AI based, and I think that this will continue.

” I’m interested to hear your opinions on Fender, which recently entered the market with the Tone Master Pro . Were you expecting that, and that are your thoughts on the TMP? Castro: “We definitely weren't surprised. I think every time you have advanced something and do so successfully – which means it’s also commercially successful – it's something to be expected.

But we don't mind competing with people. “We're a new company, so it would be a bit hypocritical for us to be upset when people try to compete with us, given that we do the same thing. At the end of the day, it's the best thing for music and for the users.

The more options there are, the better it is for consumers. “We also keep each other in check. We companies continue to push each other to improve, but it's stressful to have companies who are 20 times our size competing with us.

It's never something that we take lightly. But I think at the end of the day, it definitely helps us stay on top of our game and push ourselves to make our users happy.” Do tube amps have a future, and if they do, what does that future look like? Castro: “I think they do.

I mean, vinyls are huge now, right? Using analog gear is different from using a modeler or a plugin. I mean, look at the guitars: I don't care how many better guitars you can make nowadays or what bells and whistles they have – I still want my Stratocaster and my Les Paul. “There will always be an element of nostalgia and desire for the tactile experience of using analog gear, so I don't think it'll ever go away.

For as long as music continues to be this romantic, nostalgic thing that people do out of fashion, there'll always be room for the more traditional ways.”.