LONDON: Author and historian Zareer Masani who died on Friday aged 75 in Switzerland, was a quintessential upper-class Bombay boy. He studied at Cathedral and John Connon and Elphinstone College before moving to Oxford where he finished his doctorate in History and embarked upon a successful career as author, historian, and broadcaster. Born in the lap of luxury, his parents’ marriage symbolised the city’s famed cosmopolitanism.

Zareer’s father Minoo Masani was a leading light of the Swatantra Party, which was established in 1959 and espoused classical liberalism in response to Jawaharlal Nehru’s socialist policies. His mother Shakuntala was the daughter of Sir Jwala Prasad Srivastava, a wealthy industrialist from Kanpur who was a member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council in the 1940s. Shakuntala and Masani got married amid parental opposition from both sides.

He was senior to her by a decade, twice divorced and a Parsi. To those who knew Zareer, defiance came naturally to him. When his grandfather Sir Rustom Masani became the first Indian Municipal Commissioner of Bombay Municipal Corporation (BMC), Minoo rebelled against the pro-British atmosphere at home.

Minoo became a prominent leader of the Congress Socialist Party before Independence, only to later emerge as an eminent face of parliamentary opposition to Congress and Nehru, who was a personal friend. Similarly, Zareer’s mother, despite Sir Jwala’s proximity to top British officials, took part in the Quit India Movement and came to Bombay to work as a journalist where she met Minoo Masani. Zareer who moved to the UK in the early 1970s wrote engaging biographies of Indira Gandhi and Thomas Macaulay, expounded on the British Raj, scrutinised Nehru’s socialism, dissected Churchill’s career and examined post-independent India.

In the last few years, however, his op-ed pieces in British newspapers and ruminations on history on social media made friends and colleagues realise that it was not the same Zareer who had deposited his thesis on Radical Nationalism and All India Congress Socialist Party at Oxford’s Bodleian Library in the mid-1970s. Zareer’s writings which appeared under headlines like Koh-i-Noor belongs in Britain and not India; Britain’s Empire was a matter of pride, not guilt; British didn’t plunder antiquities distanced him from many friends and admirers, including fellow historian William Dalrymple. But this position also won him new allies.

He came to be closely identified with the History Reclaimed project, which seeks to challenge accepted versions of history. On forums like Jaipur Literature Festival, Zareer sparred with Shashi Tharoor on the art and politics of writing History calling Tharoor an entertainer and not a proper historian. Zareer, the only child of his parents, also wrote candidly about his parents’ troubled marriage and their seventeen-year-long divorce proceedings that he was witness to.

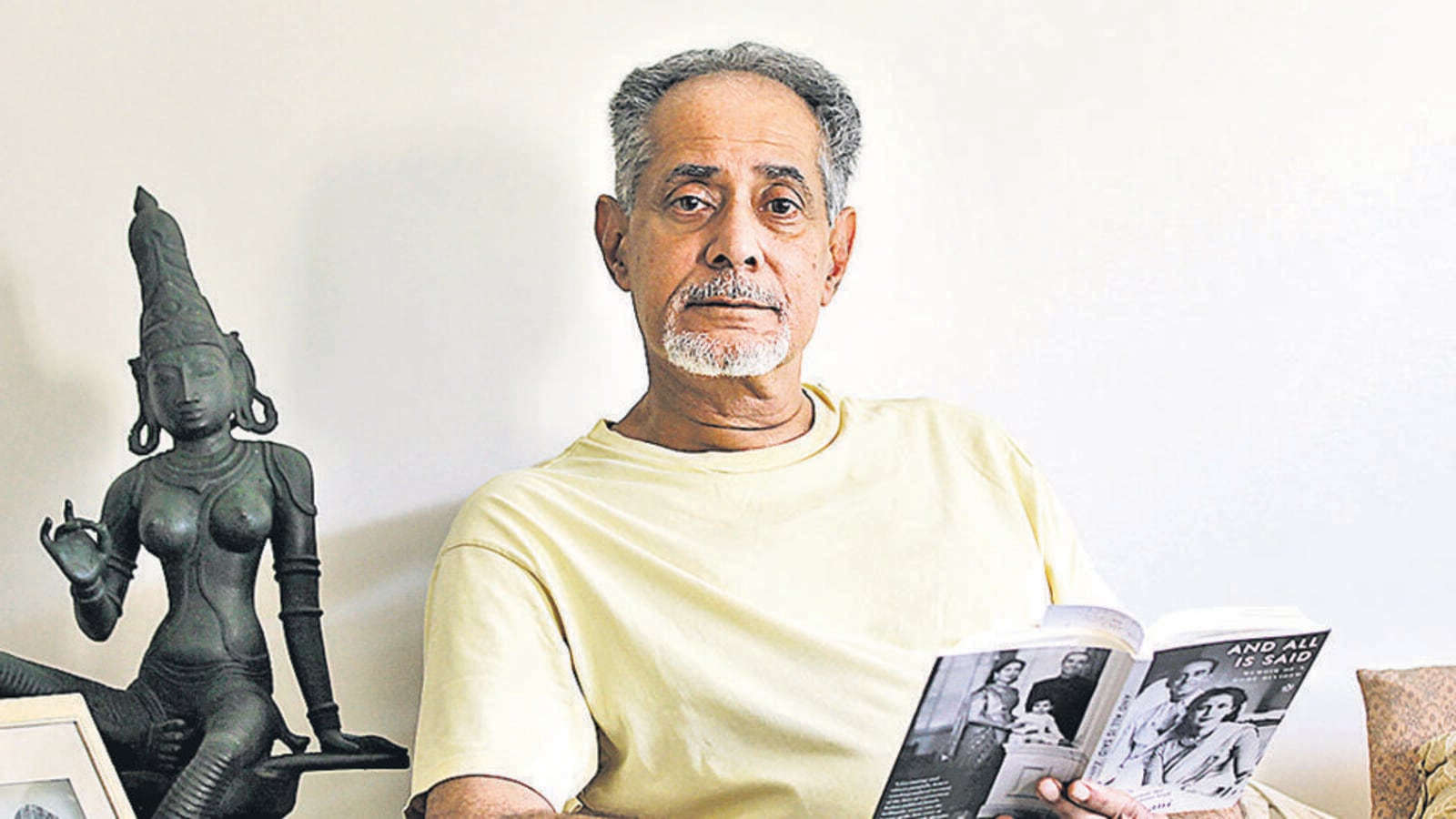

His personal story is closely interwoven with India’s political developments as he skilfully narrates in his memoir And All Is Said. When not doing the rounds of archives, producing radio shows for the BBC, or speaking at seminars, Zareer would regularly meet a small group of Elphinstonians in London. Days before he passed away peacefully in Switzerland, he reached out to a few old friends with whom he had sparred in the past and met them for lunch.

On Saturday, British historian Alan Lester posted on X: “Although we have had many disagreements I am very sad to hear that Zareer Masani has passed away. In the midst of a polarising and too often personalised & hostile culture war over colonial history & politics we at least found some common ground in our compassion for rescued dogs.”.