When my sister was eight our mother introduced her to Gerry. They talked about feminism. Gerry shot down Andrea’s argument that girls could do anything boys could do.

Afterward she was in tears. “See?“ said her mother. “You’re so intelligent, he treats you like an adult.

” The sexual assault happened the next summer. She was nine, he was 52. “Don’t tell your mother,” he said.

I was not around much by then. I’d left home at 18 and got work in Montreal. I knew that Mom was crazy about Gerry.

I was surprised she wanted to live with him in rural Ontario, having left over 20 years ago, never wanting to return. Gerry impressed me as somewhat pompous and arrogant, but he could be amusing. As a young woman I often saw the triangle of Gerry, Alice and Andrea as very close and jolly.

Lots of banter and jokes, often sexual or scatological jokes. Gerry would encourage Andrea and Mom would feign shock. I could feel the tension and darkness there, how Mom seemed helpless to ever draw the line.

Alice Munro’s husband sexually assaulted her youngest daughter. For nearly five decades, a conspiracy of silence haunted the family, and at times, One night I had a dream that my little sister was at the door of my Montreal apartment. Her eyes were wide and she said nothing, just stood there in the hall like a ghost, and raised her hands, palms out.

Bloodless strips of skin hung from her arms. I thought she had harmed herself and needed help. When I woke up I called my mother in Clinton.

Andrea was out with Gerry, everything was fine. I wanted to believe that. Later when I heard Dad’s vague version of the abuse (You know little girls, how they flirt and jump around) I ran to the phone to call my mother.

He grabbed the receiver from my hand. “Don’t you tell your mother! This would kill her!” — a familiar phrase throughout my childhood. Whenever we misbehaved it was, “You’re killing your mother!” I let it go.

It was a giant, sickening mistake that I still turn over in my mind. In the next half-hour Dad explained he’d recovered from the emotional breakup with Mom. Now they both had new partners.

He was afraid she would crack up and did not want to be blamed for wrecking her new relationship. He also thought Andrea might have made the story up or exaggerated. Last but not least, Mom was famous, and it would be a huge scandal.

Certainly there was no fear of ongoing psychological harm to my sister. No one had heard of such a thing. No one bothered to research the problem.

It was just an embarrassing thing that shouldn’t have happened. They wanted to forget about it. Dad’s new wife conducted intense interviews with the child, who began to retract and minimize the story.

In the shadow of my mother, a literary icon, my family and I have hidden a secret for decades. It’s time to tell my story. The abuse persisted for years.

So did the silence. In 1992, when my sister was 25, she tried to speak out and break free. She had some help from a psychologist and finally, some support from her family.

She wrote a loving letter to her mother, minimizing what had happened. She apologized for keeping “the secret” so long, as if that were her fault. My mother left Gerry immediately, leaving the letter on the table for him to read.

The rest of the family breathed a sigh of relief, thinking things would be different, difficult, but truthful. Mother and child reunion. No more secrets and lies.

Instead, Andrea’s needs were cast aside as frantic phone calls went back and forth between my mother and Gerry. It was too late. They’d loved each other too long! While her daughter was grown up and could live without her, Mom’s partner was threatening to kill himself.

Meanwhile he sent revolting letters to the family, admitting his guilt and defending himself for being “unconventional” sexually, and saying that my sister was a “Lolita”. I wrote to Gerry shortly after Andrea did and received a reply, which read in part: “I think that Alice and I are by and large psychological basket cases of some kind, as evidenced, amongst other things, by the rows we have ..

. they can attain awful depths of misery. And poor Andrea was dropped down into the middle of it all.

It’s quite true, as you point out, that we had a dependence on her to help us out of our rows, and ...

we didn’t see what we might be doing to her. But basket case or not, Alice is one of the greatest artists of this age. “We had a sort of a pedagogical theory to the effect that Andrea was a person, not a child i.

e. not a child as we were children in a very repressive adult world. The general idea was that no subjects, questions or language were barred .

.. I came to the conclusion that on her own initiative she was sexually interested in me .

.. The sexual event was largely in continuity with our pedagogical theory of treating children as persons.

“All I can think of day and night is that I have lost Alice and we are ruined. I would have no difficulty committing suicide except ..

. what it would do to her.” How different things would have been if 16 years earlier I had done the right thing and told Mom.

It would have been awful, but it would have been so much better. I was one of the few who had spoken to Gerry about the abuse and his vile letters. When confronted he had said, “I was crazy at the time I wrote those letters.

” But he had, true to his bureaucrat custom, typed and copied them in triplicate. Adding addenda, and even a colophon. Andrew Sabiston says the silence started when as a boy he found about the abuse by Alice Munro’s husband.

“I thought, everything would be OK. Our They were grandiose, as if written to defend in court a set-upon, mild-mannered important official from an ignorant mob. I was happy to learn of them and taped them up where Andrea had cut some to ribbons.

I had a special one he’d sent to me. Here was our proof. I gave them to the police in 2004, ultimately leading to his criminal conviction.

Later I sent all the copies to Mom, before I estranged myself for two years. She’d already seen some of them, but claimed not to have read them. “They were not addressed to me,” she explained.

We all, in our way, asked that Andrea live a lie. No wonder her pain was so palpable. I remember her phoning me.

She was in her thirties, but what I heard was a nine-year-old’s desperate need. I had been visiting Alice and Gerry, and though I could no longer stay in their house, I had lunch with them. “But they’re DISGUSTING!” she cried.

“I deserve love! I deserve love!” That cry for help will never leave me. I can never excuse the fact of my attachment to my mother, how that made me still attached to him. I told my mother and Gerry how Andrea shook with fear knowing that they were going to come to a family event, welcomed by all.

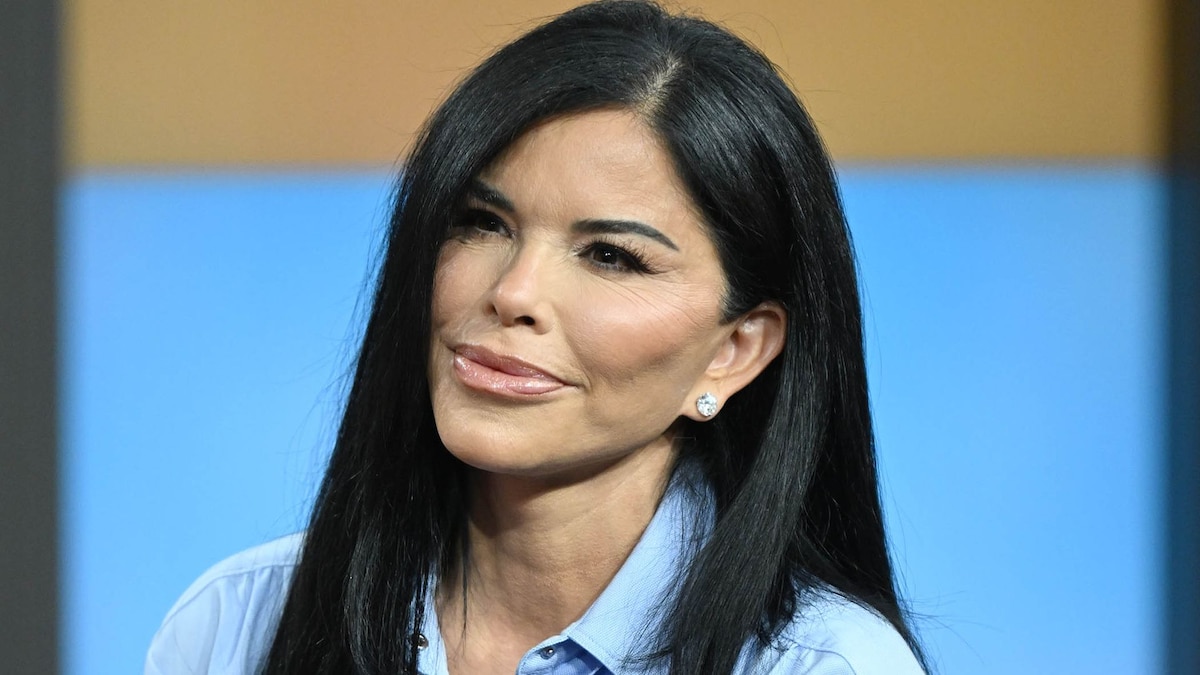

And how years later, she reacted physically with terror to seeing an envelope from either one of them, or to her mother’s voice on the radio. The family suffered from Andrea being estranged, but her silence was the perfect response to the people that demanded she pretend that everything was fine, the lie that kept us all safe. From left to right, siblings Andrea, Sheila, Jenny and Andrew.

In October 2014, I was worried about my sanity. I couldn’t live with what we had done. I found the Gatehouse, and my brother and older sister came, too.

We were not even sure we, as siblings of the survivor, deserved to be helped. We sat in a circle and really listened to each other. It was at the Gatehouse, too, where soon after I reunited with my sister.

I felt such joy then, and I still do, at the reunion. I wish my parents had acted like adults, so they could have felt this way. Now that our story is told, overwhelming waves of love have rolled in.

My family has been speaking about the unspeakable, and the beautiful messages so many have sent and posted have brought us more healing and more love. Love, and outrage. My feelings are complicated.

After Gerry died, I looked after Mom through 12 years of Alzheimer’s disease. I loved her. As the disease progressed I believed I had rediscovered the Alice who had never met Gerry, then the one who had never met Dad, who loved a big dog named Major.

There are calls to destroy Alice Munro’s books, ban her work, and revoke her Nobel Prize. But this is not about knocking down the writer or her writing. Her lovely persona may be damaged, but that wasn’t her.

Alice was a dedicated, cold-eyed storyteller. The world can acknowledge the harm she did without banning her work. It makes no sense to ban it.

Whether people love her fiction or hate it doesn’t matter. Andrea’s truth is here to stay..