By Esther Kim “Death is the mother of beauty,” the American poet Wallace Stevens writes in “Sunday Morning,” his lengthy, philosophical poem about paradise. His point confused me as a 20-year-old college student. Wasn’t a deathless heaven what everyone pined after? Our professor, Frank Bidart, explained the meaning of that troubling line, which I paraphrase: Stevens meant mortality makes life and art beautiful.

In a place without death then, is there no beauty? I believe in a corollary. Boredom is the mother of creativity. Because boredom means time.

And time in this life — to create, to think — is a luxury, a privilege. This occurred to me during "the Crash." I needed to get moving on a book project, so I decided this summer to attempt to copy author Kazuo Ishiguro’s creative process, which he and his wife carved out together and he describes in great detail for the British newspaper The Guardian.

The Crash is how Ishiguro wrote "Remains of the Day" — a brilliant, restrained novel about an English butler’s heartbreaking, misguided loyalty to his lordly employer — in four weeks. Back in the summer of 1987, Ishiguro cleared his diary. With the agreement of his wife, Lorna, who took over his household chores for one month, he wrote every day from 9:30 a.

m. to 10 p.m.

Ishiguro took an hour off for lunch and two hours for dinner. He did not see, let alone answer, any mail or go near the phone. (Today, I suppose you must avoid email, text messages, Kakao messages, Instagram and more, on top of mail.

) The idea is to "reach a mental state in which my fictional world was more real to me than the actual one," he explains. It's like method acting — method writing. Tell yourself the story.

Let it contradict itself. Just get the bones down. I attempted the Crash for one week, not one month, because I have no Lorna.

(I am Lorna?) I began to understand that boredom, intentional boredom, is a necessary prerequisite for creative writing. The constant, daily stimulation from video and audio today floods our senses and prevents us from imagining other worlds. I found myself staring at the walls, deeply bored, until I began to see a whitewashed paint splotch that resembled a swimming fish.

I didn't turn on the television once, and my mind began to conjure up characters, plots and relationships filling up that space. After the Crash, I found a similar pause again unintentionally during a hospital stay for three nights on a strict no food, no water regimen. Consider how many writers were sickly.

As a sickly child, Victor Hugo was confined to the bed. Marcel Proust’s many maladies led him to meditate on madeleines from his sick bed. Yi Sang suffered from tuberculosis.

"On Being Ill," a slim volume that pairs Virginia Woolf’s essay with her mother Julia Stephens, explores this relationship. (A practicing nurse, Woolf's mother penned "Notes from Sick Rooms" and passed away when Woolf was a child.) In "On Being Ill," Woolf argues that literature concerns itself with the life of the mind, yet life resides in the body too.

Why shouldn't the body, its foibles and feebles, also be the subject of literature? After all, we humans aren't just brain boxes with eyeballs. Bedrest in particular prompts daydreaming, which is another way of describing writing fiction, because illness forces a bedridden person to lie alone in boredom and to study that tenuous line between life and death. The break in rhythms of a "productive" life — the pain, the solitude, the boredom — are breeding grounds for imagination.

This, too, is coupled with a heightened sensitivity. Life is less casual. It demands vigilance.

Anything from dust to a blood clot could cause havoc. Life shrinks to your room, and the nurses and the physician enter through the door like a stage play. A patient must be patient.

Life removed from society feels like sensory fasting, so when I finally took that elevator down into the busy lobby, it was thrilling. There were small lessons from that one week I attempted to write fiction and the week I fasted from food. When I tasted a banana for the first time, I couldn't believe how grossly sugary it was.

I couldn't finish it. I was surprised and gladdened to find my sense of taste had grown heightened and sensitive. Similarly, if we occasionally disconnect from the barrage of video auto-plays and instant messaging, we might hear ourselves think.

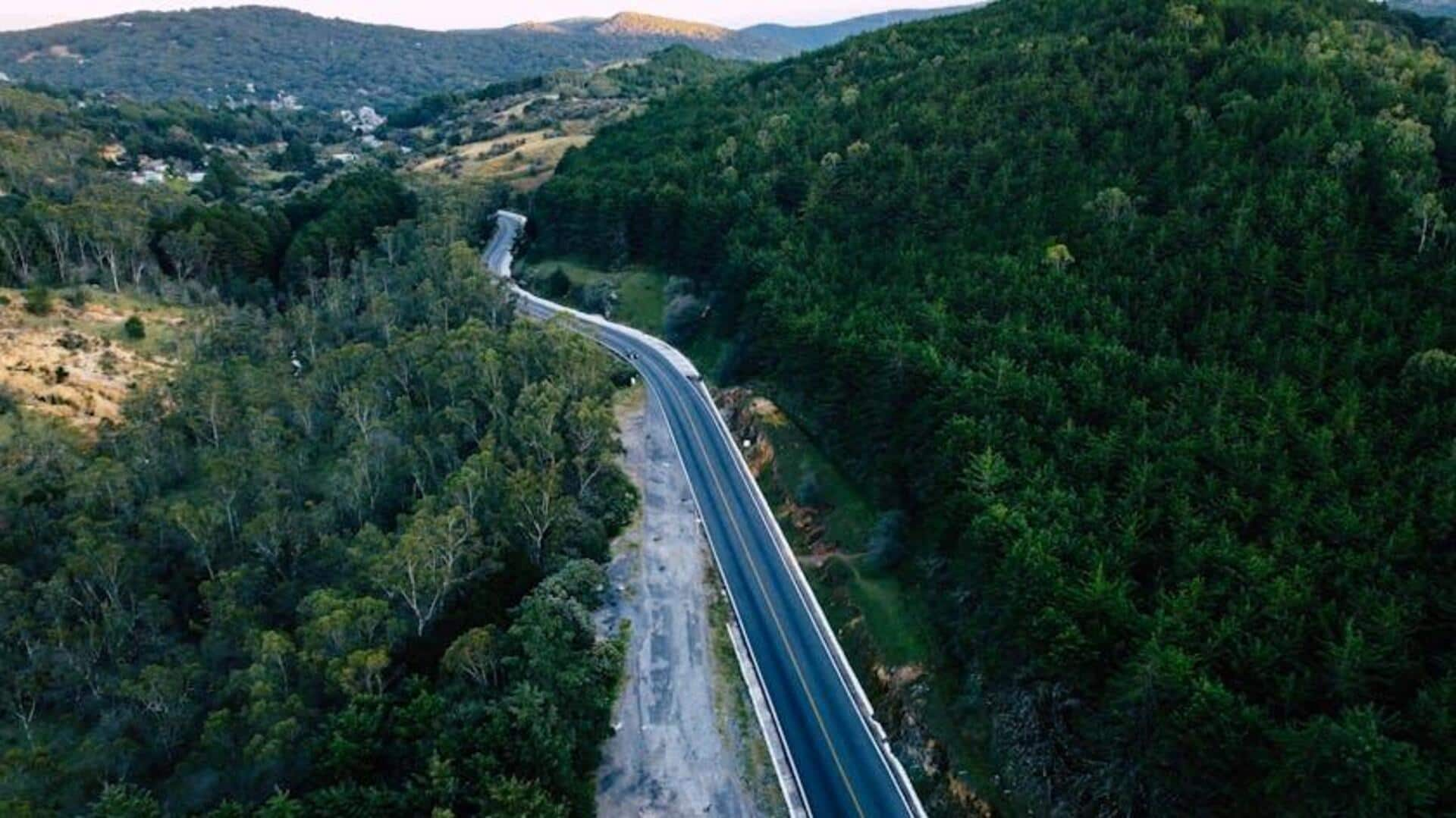

Try to fast. Go an hour or a week without the internet or screens to rest the body and the mind. Walk in nature, wherever that is, and leave the phone at home or turn it off in your pocket.

Feel its weight as a metallic, dead object. I’ll close the laptop at dusk and walk outside to the nearby stream, watching the neighborhood bats swoop and dance above the stream, feeding on night-flying insects. Trying to pay attention to how the waning sunlight shines through their fine membraned wings, paperbag brown.

Esther Kim is a freelance writer based in Taiwan. She was a senior manager at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in New York and Tilted Axis Press in London and a publicist at Columbia University Press. She writes about culture and the Koreas.

.