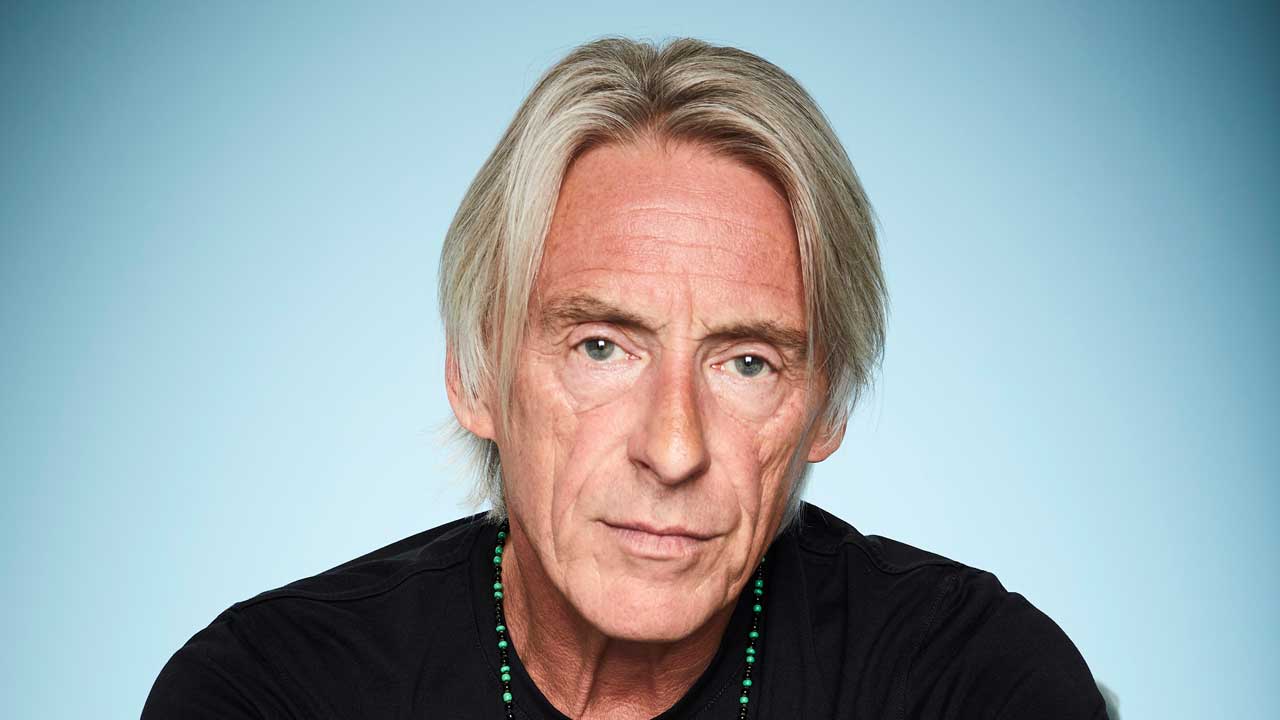

Paul Weller tends to be more misunderstood than most. It’s deeply ironic that the man responsible for some of the most innovative music of the past 40 years is so often reduced to the lazy epithet of The Modfather. His career has spanned punk, R&B, psychedelia, folk-soul, jazz, electronica and avant-rock, a spectrum that runs from brutish noise to semi-orchestral repose.

“I never, ever wanted to be ,” Weller once said. “Bless their hearts, but I don’t necessarily want to go on doing the same old thing.” This bullish determination to keep challenging himself has been the defining thread in Weller’s career.

His earliest obsessions – the Small Faces, , – were filtered into the brusque economy of The Jam. Between 1977 and ’82 the Woking trio of singer-guitarist Weller, bassist Bruce Foxton and drummer Rick Buckler created a string of killer albums and irresistible singles that earned them a fiercely loyal fan base and major chart success. Weller swiftly emerged as an uncommon songwriter, capable of articulating the blunt frustrations of working-class suburbia in a way that hadn’t been heard since Ray Davies.

The Jam could have gone on, but it was typical of Weller, eager to pursue other options, that he dissolved the band at their commercial peak. He was still only 24 when they signed off with in 1982. His next project, one that consumed him for the rest of the 80s, was the Style Council.

To preserve the integrity of it’s perhaps best that we skip that chapter of Weller’s creative journey. Suffice to say that it involved jazz-lite soul and ill-advised deck shoes. He returned to the fray with an understated solo debut in 1992.

But the following year’s , a gorgeous set of psychedelic folk-tinged songs that betrayed a love of and early , revived his career. By 1995’s , Weller had become the elder statesman of Britpop. He continued to release albums at a steady rate, never failing to make the top five.

The early part of the new millennium brought with it something of an artistic dip, though Weller recovered in fine style. The run of albums from 2008’s to his latest, this year’s age-referencing , represents the most consistently ambitious music of his life. “I’ve always been mindful of taking the writing somewhere else,” Weller has explained.

“You can’t stick in your little comfort zone." Weller has often been at his sharpest when faced with adversity. Seemingly on the slide after their poorly received second album , The Jam responded with , a bilious volley of pop-punk full of acute, character-driven observations of humdrum British life in the 70s.

The spectre of Ray Davies is apparent in the tart social critique of and , never mind the great cover of . is a tale of thuggery, but Weller could also write with a hitherto unseen delicacy; stands as one of the most arresting love songs of its era. After the previous year’s low-key debut, the Mercury Prize-nominated heralded Weller’s arrival as a truly forceful solo artist.

The overriding tone is pastoral, echoing the autumnal British folk of Nick Drake and the trippy grooves of mid-period Traffic. This reflective, almost holistic mood is perfectly expressed in the mellow warmth of the title track and the wistful epic , with rasping solo and guest vocals from his then-wife Dee C Lee. Weller hadn’t lost his edge, either.

and both bristle in a manner not heard since The Jam. Initially devised as a concept LP about childhood friends who reunite after a war, only to find themselves no longer compatible, s turned out to be less thematic. Elements of Weller’s original vision remain ( , the cover photo of a bronze cast from the Imperial War Museum), but the album instead serves as a sly treatise on class and workaday life.

is viciously poignant, while Bruce Foxton offers up his finest moment with . Bursting with melody and invention, it’s a punky postscript to The Kinks’ . Supposedly Weller’s favourite, is a potent distillation of everything he adored about British music.

are given the most explicit nod on , a No.1 single that lifts the riff of . On consumerist attack , Weller channels Gang Of Four with a dash of modern psychedelia.

Foxton and Buckler are sinuous, while Weller’s stroppy riffs are punctuated by clever hooks and, on and , a little brass. The greatest track is , a strum-along over a litany of bugbears about suburbia. Weller’s third album is an exemplar of 90s Britpop, from its ringing guitar chords and retro grooves to Peter Blake’s classic sleeve art.

Not to mention on the cover of ’s . Named after the Woking address where Weller grew up, is a mix of the reflective and acerbic. (one of two UK Top 10 hits, with ), borrows a lick from ’s , before fanning out into a bluff rocker.

The nostalgia is heightened by ’s piano turn on and . An emphatic response to all those tired Modfather clichés, is as dazzling as it is wildly eclectic. Folk, soul and psychedelia are accompanied by electronica, jazz rock and a fresh sense of experimentation that even finds room for cowbells, hornpipes and spoken-word poetry.

The beauty of it all is that it hangs together so persuasively. Then there are guests Robert Wyatt (trumpet and piano on Alice Coltrane homage ), ’s Graham Coxon ( ), ex-Jam bandmate Steve Brookes ( ) and, on the trippy , old pal Noel Gallagher. After 2018’s relatively low-key , his final album for Parlophone, Weller’s 15th studio effort saw him return to Polydor, scene of glory days with The Jam and his subsequent tenure in The Style Council.

The latter, in particular, seemed to feed into ’s partial exploration of funk and soul, typified by . Yet for all its modernist takes on vintage obsessions, the album succeeds best when Weller is at his most experimental. The seven-and-a-half minute is little short of astonishing in its scope, shifting from pop synthscapes to fractured grooves, from dirty guitar breaks to found sounds.

He takes a similar approach on songs like the sumptuous , while edges into the mystic. The clipped urgency of Weller’s tenth album suggested a return to the days of The Jam, further accentuated by two cameos from Bruce Foxton, their first collaboration since 1982’s breakup. For all its jagged brevity, though, is highly adventurous, a fact best served by the avant stylings of and the caustic soundscape , the latter featuring ’s Kevin Shields.

Less confrontational, but just as impressive, are a couple of luminous soul stirrers – and – both of which evoke the timeless spirit of Bobby Womack or Howard Tate. Weller’s burgeoning interest in free-form music is a key feature on , from the Neu!-inspired to the electronic collage of . Which is not to say he’d suddenly gone all avant-garde.

The likes of and sound like fizzy refractions of Berlin-era Bowie, while , a funky study of a man struggling with the passing of youth, refutes any notions of Weller as a man without humour. And if it’s classic craftsmanship you’re after, best head to the more tranquil, string-laden . It revels in the idea of sound as stimulant, dizzy with discovery and with a kaleidoscopic sense of purpose.

“Pop, in old money...

you know what I mean?” Weller’s directive for ’s successor was pretty straightforward: concise songs that might pass as a disparate cache of standalone singles. Eager to make up time lost to the pandemic, arrived ten months after his previous album, borrowing leftover ideas from those sessions and shaping them into something joyous and immediate. The funk-heavy title track is an effervescent celebration of music as restorative balm; occupies a space somewhere between krautrock and techno; Andy Fairweather Low joins in on the ebullient ; Hannah Peel’s artful string arrangements give flight to the likes of and , the latter co-written with Weller’s regular sparring partner, Steve Cradock.

Leaving the Style Council to one side, Weller has made other questionable turns throughout his career. , 2004’s all-covers set, is patchy at best. and , from the early noughties albums, also have their detractors.

But arguably his lowest moment is , the follow-up to the much-loved . In its defence, there’s nothing truly awful on it. But neither is there anything genuinely inspiring, just a tired-sounding retread of Weller tropes.

Perhaps most damning of all, saddled him with a reputation as the leading exponent of lumpy dad-rock. Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox! Freelance writer for since 2008, and sister title since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years.

Other clients include and . Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the and in the Parallel Universe slot.

Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip. "I now realise that to save the badgers, you have to save everybody": Brian May to host new BBC show The Badgers, The Farmers And Me “It’s the definitive Oasis album.

It has the spirit, the arrogance of youth.” Thirty years on, Noel Gallagher looks back at Oasis' era-defining debut album Definitely Maybe A convoy of 55 Harley Davidson motorbikes has delivered Lemmy's ashes to Nottingham's Rock City.