As we reach the end of the summer season, it's time to consider good books. The Post and Courier asked its regular reviewers what titles have stood out so far this year. Here are their answers: KNIFE.

By Salmon Rushdie Catherine Holmes The book that I can’t get out of my mind this year is Salman Rushdie’s “Knife.” Rushdie has often made the point that storytelling and self-mythologizing are at the center of our being: “I think stories are what we are, we all live in our stories of ourselves.” The bedrock of “Knife” is Rushdie’s belief in what turns out to be a false but beautiful story: he has come to trust that he has outlived earlier threats to his life.

He has been out, openly on the world’s stage, living and loving freely. Then a spectre from the past comes to life: the Ayatollah’s fatwa. “Knife” opens with an attack on Rushdie at the Chautauqua Institute, one that leaves him blind in one eye and fighting for life.

The last thing his right eye would ever see was the “squat human missile” running toward him. After the attack, he asks himself if his happiness can survive such an assault. It’s not giving away too much to affirm that the answer is yes.

“Knife” ends with a return to the scene of the crime. Rushdie and his wife, the poet Eliza Griffiths, stand on the stage on the spot where his assailant attacked. A burden lifts, and he feels light and whole.

—Catherine Holmes LULA DEAN’S LITTLE LIBRARY OF BANNED BOOKS. By Kirsten Miller. Jonathan Haupt, director of the Pat Conroy Literary Center in Beaufort.

Smart, subversive, humorous, and tender, Kirsten Miller’s “Lula Dean’s Little Library of Banned Books” is relevant reading for anyone invested in understanding contemporary controversies surrounding the right to read freely. Miller’s novel pits an attention-seeking smalltown busybody with political aspirations against an idealistic former cheer captain turned school board president (and her tenacious daughter with world-saving tendencies) in a battle over censorship of library books and the democratic ideals interwoven with equitable access to diverse and representative literature. Miller deftly avoids oversimplifying complex issues or dismissing the rights of families of make informed choices in their own beliefs, but she also illuminates the risks of the erasure of ideas and the motives of those so eager to censor the histories, identities, and experiences of others.

Promptly becoming a favorite among southern book clubs in particular, Miller’s clever and compelling narrative is more than just timely. Like so many of the banned and challenged books mentioned and defended in its richly rewarding plot, this novel is absolutely essential reading — one of the best books of 2024 so far. —Jonathan Haupt MEDGAR AND MYRLIE.

By Joy Ann Reid. Rosemary Michaud Joy Ann Reid’s “Medgar and Myrlie” left a mark on me. As someone who vividly remembers the season of horror when John Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy and Malcom X.

were assassinated, I am ashamed to say that Medgar Evers was just a name to me, and apparently to many others, according to Reid. Yet he was the first in that group, brutally shot in the back outside his home in Jackson, Miss., on June 12, 1963, while his wife Myrlie and young children cowered inside.

Medgar did his share of traditional organizing, later becoming part of MLK’s program of non-violence, but what struck me most was his raw courage as he travelled the highly dangerous backroads of Mississippi, essentially alone, begging his frightened neighbors to join the NAACP. His statement that he loved the South, that he would not, like others, leave his home state, but stand and fight, deeply moved me. The decision proved to be his death sentence.

Reid writes with a kind of controlled rage, that infected me as well. The next time I am in Washington, I plan to visit Medgar’s grave. As a World War II veteran of the U.

S. Army, he is buried, at President Kennedy’s insistence, in Arlington National Cemetery, a totally appropriate resting place for this American hero. —Rosemary Michaud Story continues below MY FRIENDS.

By Hisham Matar. Simon Lewis I'm not surprised to see that Hisham Matar's "My Friends" has just been longlisted for this year's Booker Prize. A sustained meditation on the value of personal friendship under strained political circumstances, Matar's new novel focuses on three exiled Libyans' experience from the 1980s through to the revolutionary aftermath of the Arab Spring.

While the action is driven by recent Libyan political history, its geography is marked as much by the narrator Khaled’s nostalgia for London as for Benghazi. In fact, Matar includes an unusual thank you in his Acknowledgments: “This book owes much to London,” he writes, “as do I.” Similarly balancing the Libyan political focus, Khaled’s cosmopolitanism weaves together the various threads of British, European, African and Arabic literature.

Unlike his more nationalist-minded friends, Khaled finds himself becoming less Arab over time, a process Matar describes in a typically poetic phrase as being “like a wall gradually losing its color to the weather.” The book is beautifully, even lyrically written, but its short, dense chapters keep the action moving at a very brisk rate, unfolding as vividly as the pages in an old-fashioned photo album. —Simon Lewis JAMES.

By Percival Everett. Melinda Copp “James” by Percival Everett is a reimagining of Mark Twain's “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” told from the perspective of Jim, the enslaved man who accompanied Huck on much of his journey on the Mississippi. I had a teacher in middle school who loved Twain, and we read Huck Finn in class.

This was the first time I remember doing such a close read of any novel, and I'm not sure how much I appreciated the exercise at the time. But 30-plus years later, I was very excited to revisit the story through Everett's eyes. James is a reimagining of the highest order.

Everett has added a compelling new dimension to the classic tale, giving the character Jim agency, keen intelligence, and, through his experiences, deep insight into America's greatest flaws. The story is gripping and frightening and triumphant. Once I started reading it, I could hardly move.

And when I finished it, I jumped up and pumped my fist in the air. —Melinda Copp And one more for good measure. Though not a 2024 release, Bill Thompson adored this travel memoir by New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik, who considers a year living abroad in Paris.

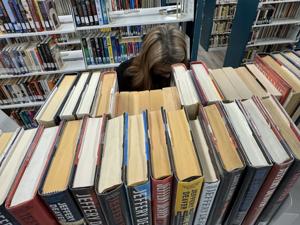

PARIS TO THE MOON. By Adam Gopnik. Bill Thompson One never knows what gems may be entombed beneath a mound of lesser work at a library book sale.

Having become familiar with long-time New Yorker staff writer Adam Gopnik upon reviewing his splendid “The Real Work” (2023), I snatched from the stacks his 2001 memoir “Paris to the Moon.” My expectations were high. They were exceeded.

Gopnik’s book recounts a year’s residence in Paris with his wife and their infant son. In the tradition of Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, James Baldwin, and A.J.

Liebling, he chronicled not only the ineffable romance of an American in Paris, but all the joys and headaches of daily life — first conveyed in his “Paris Journal” in The New Yorker. Gopnik is closest to Liebling in terms of the wit, verve, and sophistication with which he weaves the fascinating and the mundane. Even French writers were impressed.

As one wrote in the weekly magazine Le Point, “It is impossible to resist delighting in the nuances of his articles, for the details concerning French culture that one discovers even when one is French oneself.” Such is the measure of a great observer and prose stylist. Magnifique, first page to last.

—Bill Thompson Email Sign Up!.