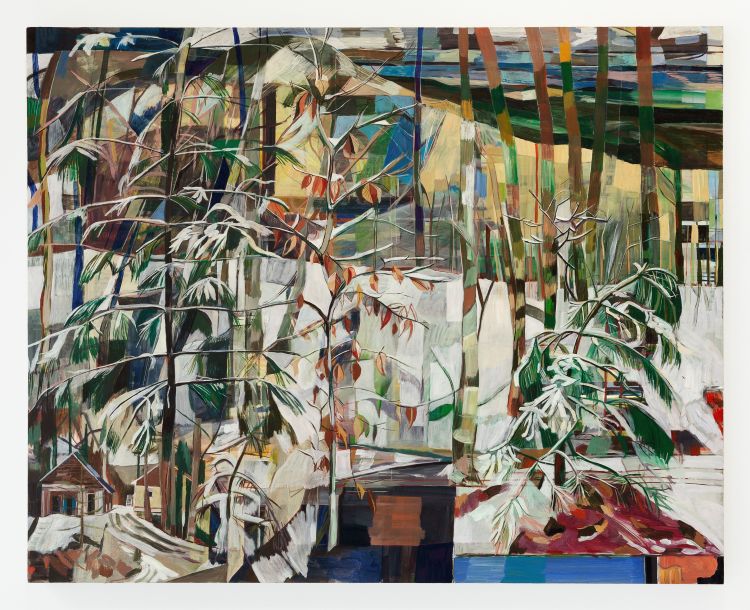

“White Pine Walk” by Jay Stern, 2024. 48 x 60 inches, Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Grant Wahlquist Gallery It’s a rich season for work by gay artists.

We started with the Ogunquit Museum of American Art’s Anthony Cudahy survey, “ Spinnaret ,” which comes down today. Two shows by gay artists are on exhibit at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockland: “Nature Cult, Seeded | Donald Moffett” and “To Whom Keeps a Record | Arnold J. Kemp” (both through Sept.

8), which I’ll report on next week. WHAT: “Jay Stern: Awning” WHERE: Grant Wahlquist Gallery, 30 City Center, 2nd Floor, Portland WHEN: Through Aug. 17 HOURS: 11 a.

m. to 6 p.m.

, Wed.-Sat. (by appointment other days) ADMISSION: Free INFO: 207.

245.5732, grantwahlquist.com They don’t all tackle specifically gay themes.

Moffett, though well known for his art about AIDS, gives us instead a cri de coeur for the environment, focusing on endangered bird species in “Nature Cult.” And Kemp’s show is as much (or more) about being Black as being gay. But an argument can be made that all these shows deal with a kind of marginalization of a group (or species) that seems to be escalating rather than diminishing.

Currently at Grant Wahlquist Gallery in Portland is “Jay Stern: Awning” (through Aug. 17). Ostensibly, it’s a landscape and interiors show.

But the subtext here arises from a particularly LGBTQ+ point of view. You could say that it is a metaphor for how gay people often must hide in plain sight, depending on the circumstances of the moment. On the face of it, “Awning” is an unabashedly beautiful Maine pastorale.

Stern, who arrived in Maine in 2021, is obviously smitten, painting rural scenes of houses secluded in the woods, clothes drying on a laundry rack, his kitchen, a country road. They are lush, sylvan and green, and we want to move into them. Yet as we begin to do so, entry seems, if not barred outright, at least elusive.

It’s at that point that we realize Stern has devised an elaborate charade that complicates access. If we want in, we’re going to have to work for it. He accomplishes this tease in myriad ways.

First, with his hybrid blend of abstraction and representation. Even as we’re proffered a seat at any of several benches in “Hope Park,” for instance, we realize that the ground we must traverse to get to them is abstract and unstable. Stern also fractures the grassy surface by subtly dividing the canvases into sections, each observed from a different angle, further disorienting any would-be interlopers on the scene.

And there his use of color and weirdly transparent voids that muddle our understanding of what is what, not to mention the sudden precarious drop-off in the foreground that looks as though we must leap over to land in the scene. “House on Mechanic St.” by Jay Stern, 2024.

48 x 48 inches. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Grant Wahlquist Gallery “House on Mechanic St.

” puts a thick stand of trees between viewer and the house, as well as a similarly shifting foreground. When you’re up close to it, it’s hard to make out the house amid the cacophony of color and the back-and-forth of planes. He does this again with “Exposed Fall Houses” (we’ll see shortly how the word “Exposed” is significant), this time, however, giving the view of the house a jewel-like faceting by treating the spaces between the trees differently.

The effect is a warping of logical space we might experience when looking through a diamond. In his sectioning off of surface Stern fills each quadrant with frequently incongruous juxtapositions. “White Pine Walk” includes a house at lower left and a lakeside landscape at lower right that barely seem to belong to the overall scene, which itself appears to be occurring during several seasons simultaneously.

In most paintings, he agitates the surface with color and quick, Cézanne-like brushstrokes. From top to bottom, a single sapling can morph abruptly from brown to green to terra cotta to black to khaki to cream. Why paint them this way, especially if it’s not to depict dappled light or some other phenomena? It scrambles our brain, making its quest for explanation and reason chimerical.

“Forever Suspended in a Doorway (Self Portrait)” by Jay Stern, 2024. 65 x 80 inches. Oil on canvas.

Courtesy of Grant Wahlquist Gallery There’s such agitation on Stern’s surfaces, in fact, that they can induce dizziness. The sectioning is perhaps clearest in “Forever Suspended in a Doorway (Self Portrait),” a view of his kitchen with windows on either side of a stove. At right is a counter that exists in a logically level perspective.

But at left the counter is weirdly foreshortened. Three dismembered hands touch the surface of the stove (a reference to a friend who perished in a house fire and a reminder to test the burners three times before leaving home to be sure they’re off). And above the stove is the self-portrait — no more than a white silhouette of his head against a similarly abstracted background.

Stern’s skewing of angles can make you feel woozy. Why the tumultuous composition and the ceaseless tension between abstraction and representation, between visual invitation and rejection? It’s an effective (and poignant) way of representing the condition of being gay in a heteronormative world that continues to consider gay people — despite greater acceptance — as aberrant or part of an “alternative” lifestyle with an agenda. (If you’re naïve enough to think this condition is in the past, consider Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’s concurring opinion in the case that overturned Roe v.

Wade in 2022, where he encouraged his fellow justices to “reconsider” rulings that codified rights to contraception access, same-sex relationships and same-sex marriage.) These paintings embody the hide-and-seek many LGBTQ+ people perform daily, choosing what to reveal and what to conceal, what to say and what to keep silent, which impulses to indulge and which to repress. Stern’s paintings are still beautiful.

But they are also a little heartbreaking. “Why should we let you in,” they seem to ask. “Can I trust you? What will happen if I do?” Exposure — there’s that word again — may not always be a good thing.

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland.

He can be reached at: [email protected] Modify your screen name Please sign into your Press Herald account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe .

Questions? Please see our FAQs . Your commenting screen name has been updated. Send questions/comments to the editors.

.