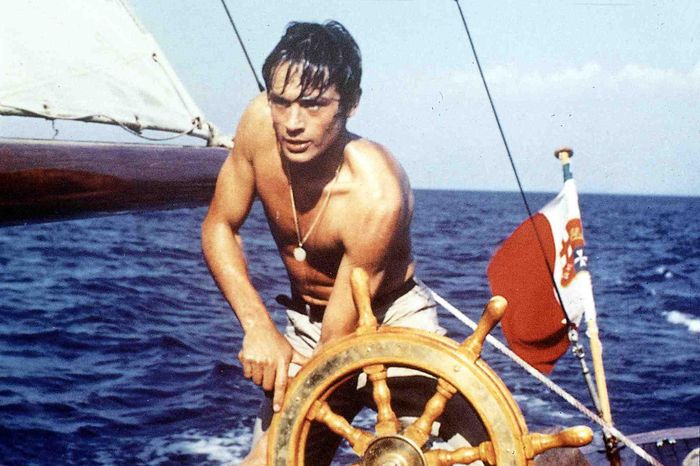

Forgive me if I talk about Alain Delon ’s face for a minute. In truth, it’s hard not to. Certainly, in the early years of his career, that visage was more than a face; it was an existential fact.

The feline eyes, the elegant cheekbones, the mouth both delicate and full — Delon was often even prettier than his female co-stars, who themselves weren’t exactly chopped liver. Filmmakers and audiences seemed to understand this, and that disruption — the transfer of onscreen physical beauty, and even vulnerability, to the male — created an exciting slipstream of ambiguity. In one of his first major roles, Christine (1958), Delon plays a womanizing Austrian second lieutenant who falls for Romy Schneider’s young singer, and he’s treated as a forlorn object of desire, caught between different women.

When we first meet him, he’s ending a torrid love affair with a married baroness. He meets Schneider’s character when he’s asked to accompany a fellow officer on a date, and the two don’t immediately get along. Her desire, however, charms him and wins him over.

(Delon’s onscreen persona, like Cary Grant’s, often had women pursuing him — not the other way around.) But it’s a doomed romance, as the baroness’s jealous husband soon enters the picture. The film plays off Delon’s fragility.

He feels as if he’s perpetually on the edge of romantic disaster and even death. A reluctant Casanova; a moody, almost passive figure — it’s as though his physical appeal were somehow connected to his melancholy. The beauty of the face creates a kind of shield.

You can read into it sadness or cruelty or indifference. That’s not to say that Delon wasn’t a skilled actor. He was, but he also understood for much of his career that anything he did onscreen would be anchored to his physical beauty.

In that sense, few directors used him as well as Jean-Pierre Melville, who cast Delon in three of his greatest policier s. In the now-iconic Le Samouraï (1967), he’s the pathologically quiet and patient hit man Jef Costello, who lives in monklike austerity and kills with surreal precision. The film’s story turns on a manhunt for Costello after his crime is witnessed by a nightclub piano player (Cathy Rosier).

But she refuses to identify him. Not a word was exchanged between them — only a glance. In other words, she saw his face and couldn’t bear to see it harmed.

This is the genius of Melville, of course, conveyed in glances and gestures: to turn the most elemental of impulses into the stuff of high drama. Luchino Visconti, that great connoisseur of faces both male and female, also cast Delon in two of his greatest films, in two surprisingly physical parts. In Rocco and His Brothers (1960), the actor plays Rocco, the angelic working-class southern boxer who finds himself at odds with his elder bruiser brother, Simone (Renato Salvatori).

The troubled and violent Simone has fallen out of favor and resents his younger sibling, who is both the better boxer and the better human. In one of this wild melodrama’s most agonizing scenes, the two men fight over the fate of the woman with whom they’re both involved. Rocco’s gentleness, his delicacy around his brother, has defined him for so much of the movie.

Their fight — an extended, knock-down, drag-out affair — is brutal and cataclysmic. Watching Delon get hit, we want to yell out, “No! Not the face!” But what we really fear for is his soul. In Visconti’s world, these things are not unconnected.

In Visconti’s masterpiece, The Leopard (1963), Delon plays Tancredi, the dashing nephew of the Prince of Salina (Burt Lancaster), whose revolutionary exploits at the side of Italian independence leader Garibaldi planted the seeds of his family’s survival. Tancredi comes home a war hero, falls for the beautiful daughter (Claudia Cardinale) of a local politician, and soon becomes a solid member of the new upper-middle-class Establishment that will gradually replace the ossified Sicilian nobility. Visconti shoots Delon in the film’s first half as a force of nature, striding through the elegant, unchanging halls of his uncle’s villa; the other members of the family are usually sitting or standing still as if they’ve already been trapped by class and history.

But Tancredi bounds through frames and rooms, charges with his horse through mountain passes, and drifts through the rooms of abandoned mansions. Thus Visconti represents a historical idea — the newfound social mobility that will do away with the old order — as a physical one, rooted in Delon’s freedom of movement and his cheerfully seductive glances. Late in the film, speaking of Tancredi and his family’s past, Lancaster’s character muses, “There’s no need to tell you of the history of the house of Falconeri .

.. My nephew’s fortune does not match the grandeur of his name.

My brother-in-law was not what one calls a provident father. The sumptuousness of his life impaired my nephew’s inheritance. But Don Calogero, the result of all these troubles .

.. is Tancredi .

.. Perhaps it is impossible to be as distinguished, sensitive, and charming as Tancredi unless ancestors have squandered fortunes.

” It’s an interesting and moving little speech, and it speaks to the brilliance of Visconti’s casting, for so much of The Leopard turns on Tancredi’s singularity. The prince even dismisses his own daughter’s love for Tancredi; he understands that this young man is destined for greater things and that therefore he must have a more suitable wife. (Which he finds in Cardinale, another ’60s avatar of divine onscreen beauty.

) In Tancredi lies the survival of an entire class. Who better than Alain Delon — dashing and with a hint of growing aloofness — to represent a man of such multitudes? Delon’s life had been an unusually harsh one before he was an actor. He had been abandoned by his parents at the age of 4, but they did, he later recalled, reappear in his life long enough to sign his papers for the French Army.

As a result, he wound up fighting in Indochina in the 1950s. Before being discovered randomly at Cannes in 1956, he had been a butcher and a naval infantryman and had spent months in military jail before being dishonorably discharged. He never quite gave up his roughneck ways, even after achieving stardom.

He enjoyed the company of mobsters and liked to talk about how much he enjoyed the company of mobsters. In 1969, he got entangled in a truly bizarre (and ultimately unresolved) sex-and-murder scandal regarding the extremely suspicious death of a former bodyguard. In later years, he gained a different kind of notoriety for his far-right views, which toned down the adoration some had for his earlier work; his lifetime-achievement award at the Cannes Film Festival in 2019 was met with protests.

It recently emerged that before he died, the 88-year-old Delon requested that his dog be euthanized and buried with him — a crazy demand that the actor’s family wisely chose not to honor. Still, Delon’s retrograde politics didn’t seem to stop new generations from rediscovering the sublime work he did with Melville or some of the brilliant thrillers he made with the likes of René Clément (including 1960’s Purple Noon , still the best adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley ) and Jacques Deray (in particular 1969’s The Swimming Pool , which became a major repertory hit Stateside in the plague-damaged year of 2021).

Perhaps Delon welcomed the fact that all his tough-guy posturing tempered the almost-feminine quality of his image. Maybe that’s why he wasn’t particularly interested in hanging on to that image as he grew older, allowing instead the jowls and the wrinkles to settle in naturally and gracefully in later years. In the 1970s and ’80s, he seemed to even relish playing parts that allowed him to be somewhat ordinary.

In José Giovanni’s Two Men in Town (1973), he plays an ex-con who is rehabilitated and mentored by a prison counselor played by Jean Gabin as he enters the real world and tries to make an honest living. “Have you seen his eyes?” a prison official asks Gabin early in the film, noting that all he sees in the Delon character’s face is “hatred and contempt.” “Yes, but there’s tenderness there as well,” Gabin responds.

It’s hard not to feel as though the whole exchange symbolizes the effect of Delon’s presence, the sense that, in it, you can simultaneously read both cruelty and vulnerability — and the further sense that if both of these forces can exist in the same face, then maybe they’re not so different after all..