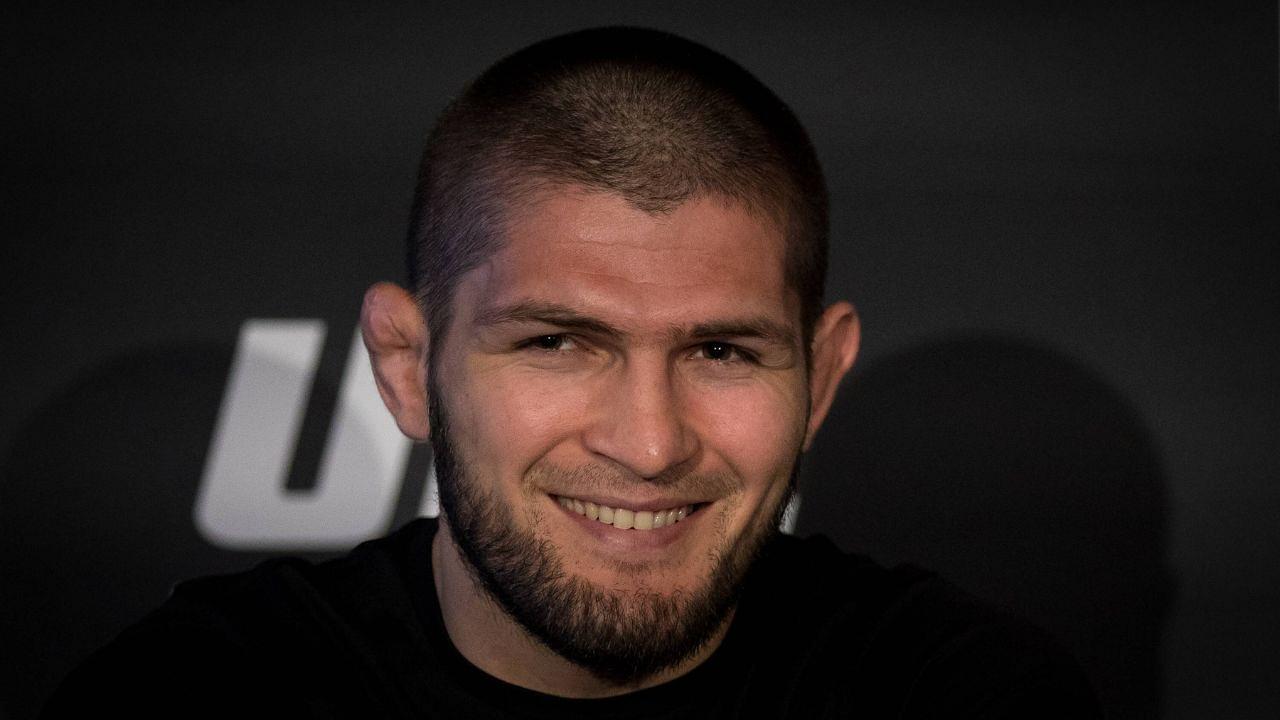

“Please keep the memory alive,” Olga Horak told The AJN two years ago. That request is more poignant than ever after the beloved Holocaust survivor, author and artist passed away last week, days after turning 98. Horak was passionate about education and continued to volunteer at the Sydney Jewish Museum, of which she was a founding member, right until the end.

Incredibly, she recounted her survival story for the last time the week before her passing to a group of school students – including her own great-granddaughter. “The best way to continue her legacy is by speaking out and fighting back at the mere sniff of antisemitism, whether you are Jewish or not,” Horak’s grandson Jonathan Sankey told The AJN. Sankey said she continued to follow the news every day until she died.

“When she saw people flying Hamas and ISIS flags she was devastated that this could happen in her beautiful home of Australia, when she thought she left all of that behind,” he said. “More than anything she was disappointed in our government, that our racial and anti-discrimination laws were not worth the paper they’re written on.” When Horak was at home, Sankey said most of the conversation revolved around the Holocaust and what it means to be Jewish.

“She went through these unimaginable horrors, but more than anything she just got on with it. There was no victim mentality. She came to Australia with her family all dead, no money, no government assistance and only three months later had a factory and a business with no government or community support.

“She had the exact opposite of a victim mentality – she was a victor.” Born in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, in 1926, Horak was 14 when the war broke out in 1939. While in hiding in 1942, the family were betrayed and sent to Auschwitz.

Horak’s father and grandmother were sent directly to the gas chambers. During the winter of 1944-45 Horak and her mother marched for hundreds of kilometres to Dresden, where they were then transported to Bergen-Belsen. Despite suffering from typhus and diphtheria, Horak survived to see Bergen-Belsen liberated on April 15, 1945.

Tragically, her mother died in her arms the next day. In 1949, Horak and her husband John, also a survivor, arrived in Sydney to begin a new life. “She loved this country,” said Sankey.

“She really embraced and loved being Australian and gave back to the community as a result.” The Sydney Jewish Museum paid tribute to Horak as “an exuberant force of life”. “For over 30 years, she shared her story of survival with thousands of people from all walks of life, dedicating her life to speaking for those who had their voices taken away.

So many who had the privilege of meeting her describe the experience as life-changing. “Her life story and message about the dangers of hate will live on at the Museum so that future generations can continue to learn from her.” In a letter to Horak’s family, NSW Premier Chris Minns said she will be remembered as “a strong and resilient woman and a remarkable Australian”.

“She chose to become a compassionate and articulate voice for her people, ensuring the atrocities of the Shoah would never be forgotten,” he said. Executive Council of Australian Jewry co-CEO Peter Wertheim described Horak as “a communal treasure”. “Having overcome so much trauma, she made a new life for herself in Australia and dedicated her final decades to teaching thousands of students, political and communal leaders and many others about the timeless and universal lessons of the Shoah,” Wertheim said.

Horak was the patron of the Australian Association of Jewish Holocaust Survivors & Descendants, with president George Foster describing her as a “wonderful, caring, determined woman who was always willing to give her time to speak of her experiences and teach the lessons of prejudice and racism”. “She was forthright in her opinions, but always truthful and honest,” he said..